I thought I might start today with a confession, the kind of thing that could get me in trouble with any number of the wielders of self-righteous bullhorns that seem to constitute so much of our public life:

I think the debate over trans kids in sports is perhaps the dumbest of all of the dumb issues that plague our moment.

It is actually difficult for me, given the constraints of the English language, to articulate how stupid (and yet how completely representative of American culture) this issue is. But I'm going to try.

Often, one prefaces the kind of screed I'm embarking on with the phrase, "I'm sorry, but…" as in "I'm sorry, but I just can't take this idea seriously…"; however, I cannot do that because I am not sorry. I sincerely think that if you are so concerned about the idea of "fairness" surrounding the efforts of a bunch of twelve year olds wearing matching clothing to hurl a ball into a bucket that this is the issue you allow to determine your view on a deep question of human existence, then you have fucking lost your marbles.

Reading about the sturm und drang involved in this debate makes me want to clutch my head in agony and scream into the void.

If you are someone for whom this debate is important, here are a couple of things I'd like you to know.

Your kid is not going to be a professional athlete.

Even if your kid were going to be a professional athlete, competing against someone with some sort of "genetic advantage" would actually be a benefit for them, because it would raise the level of competition which they have to face, thereby hardening them for the arduous road ahead.

You have no idea what you're talking about when you try to talk about "fairness." To you, fairness is "my kid isn't getting to win all the time." But, you see, what you don't understand about fairness, you blockhead, is that all fairness is a matter of perspective. To make this point clear, let's take an example from another realm of existence. For a child born into poverty, the fact that other children's families have more money – which, given the obvious boons of good diet and nice vacations and violin lessons and private preschools and tutors and college trips and parents buying you cars and basic social entrée, offers a massive, tangible advantage in virtually every aspect of a child's life – for a poor child, the fact that other families have more money is unfair. So, if you really believed in "fairness" for children, you would support a 100% estate tax system, under which when adults died, their money would be evenly distributed among all children, rather than just hoarded for their own children, thus ensuring that every kid had a fair start. But you don't really care about fairness, do you. You care about your kid in their blue laundry with the number on the back putting the ball in the hole so you can feel that rush of superiority about your genetics and parenting techniques.

And as if it's not bad enough that this idiotic preoccupation with trans kids in sports is so pervasive, there's also the deeply depressing fact that it's so quintessentially American.

Because the American obsession with sports – and I say this as someone who played sports at the college level and still continues to play "competitively" (I use the scare quotes because, given my age and the age of the men I'm competing against, that word, "competition," doesn't quite carry the resonance it once did) – the American obsession with sports is insane.

Here's a fun experiment. Try watching a pro football game, or baseball, or basketball, or whatever your jam is, as if you are an alien who has just recently landed on our benighted planet. Honestly? This is some weird shit, man.

Not only are there grown men killing themselves to put a spherical object in a net or move an obloid down a field according to rules so byzantine that they literally cannot be explained in the time it takes to play an entire game, there are also other grown men whose job it is to tell us what's happening in the game as we watch it. They dress in suits and ties and describe the game to us as if we could not see it, but we can see it, and they know we can see it, because they're on the same TV as the game. There are light shows and fireworks and women dancing around in skimpy clothes and commercials howling at us that we don't really know what fun is until we're wagering money on props bets while we cheer so wildly that we dump our chicken wings into our pitchers of beer and at something called "half time" a man comes out and balances a chihuahua on his head while he rides a unicycle. There are entire multi-million dollar industries replete with conferences and young folks dying to make this their "career" devoted to counting up how many "points" a woman scored during the season, or to how, and where, and the number of times a man smashed into something called the "ball carrier," perhaps even "sacking" them and causing a "fumble," or, my god!, even creating the circumstances for a "pick six" to occur, at which point all the other men run to a colored area at one end of the field and pose as if they are badasses even though they're wearing colored tights and helmets featuring a drawing of a cat.

None of which is to say, of course, that America is uniquely weird in this respect.

Other cultures are equally bizarre in their own ways. And I happen to like American culture. I even, within the bounds of sanity, like American sports. If I wanted to live somewhere else, I could. If I, for example, had the desire to live under a totalitarian regime bent on the destruction of other cultures on the road to global domination, I could move to China, and if I wanted to live under a heavily-armed caliphate bent on the imposition of a nonsensical ancient religion, I could move to Texas.

Perhaps this last jibe is a bit too much, but to really understand its psychic source, you have to know that I grew up in Colorado. During my childhood, particularly in the resort towns that were my milieu, there was a great deal of resentment of Texas and Texans, because the economy in that state was flush with oil money, and many of its citizens invested that money in Colorado because of our naturally beautiful mountains and forests and ski resorts, buying up land and vacation homes and flooding our fine state with their silly accents and inability to drive in the snow.

It is a fairly natural reaction, I think, when the land one grows up in is being purchased by hordes of wealthy outsiders, to build up a resentment against them; and, as a kid growing up in a place in which the public restrooms were festooned with witticisms such as "Here I sit, my buns a flexin, giving birth to another Texan," I must admit that I was influenced by the prejudice all around me.

All of which is to say that I, like everyone, was deeply formed by the culture in which I swam (note here, that although I just invoked swimming as a metaphor, it also brings to mind the fact that it's possible to swim just because it's fun, instead of swimming to prove that you can use the most bizarre motion imaginable to propel yourself back and forth across a pool for the purpose of crushing your foes (who are also only fourteen years old) under the strokes of your incredible talent), just as millions of red-blooded Americans are formed by the idiotic worship of sports culture around them and allow it to become the mode of thinking through which they try to make decisions about something like another human being's ability to live their life according to their own lights, be those in terms of gender identity or any other.

And all of which brings us one of the many important questions lying beneath our feet: what is it in the American culture and identity and soul that makes us act in the mad ways we do?

There are times when I think that to try to understand American culture is to try to understand a void, or a yearning. Put differently, the question may not be what our culture is, so much as what it lacks.

However, before I continue, I should note that what we mean when we talk about "American culture" is nothing if not contested ground. In what follows, am I talking about American women? Am I talking about American people of color? Or am I simply talking about American white dudes?

It is reductive, and easy, and in some sense not incorrect to say only the latter. A great deal of what afflicts us now, as well as a great deal of the culture I tend to use to think about it, centers on American white dudes. The way we tell our history often centers on white dudes, and the issues that we (by which I mean I) tend to present as "American" are often very clearly often the issues of white dudes.

In part, this is unavoidable, because I am, yes, an American white dude. And I have written at some length about the issues guys who look like me are afflicted with (and thereby inflict upon others) here and here and here and at book-length elsewhere.

But it is in part unavoidable because, like it or not, white-dudeness has formed American culture to such a great extent that not only has it, I believe, deeply influenced the habits of thought and action of Americans who are not white and/or male, it has also, I believe, formed our country to such an extent that if one wants to shift it away from being a white-dude-oriented place, one must first understand the constituent elements of that place, some of them in their full, bloated, insecure, white-dudeness.

To take just the most obvious example at hand, what do Donald Trump and Elon Musk and J.D. Vance and Stephen "I look like a goddamn vampire" Miller and Steve Bannon and the rest have in common? Yep. Say it with me: they're all…flaming subhuman assholes, but also white dudes.

Of course, it could also be the case that trying to understand them is mostly just a waste of time. Who knows? But William Friedkin's 1985 film To Live and Die in L.A., which is a film that seems to me to demonstrate a really tremendous comprehension of the nature of the void at the center of the American soul, is about white dudes, so I thought I'd offer the disclaimer.

Friedkin is an extraordinary and fascinating filmmaker, and made some of the greatest American films of the 1970s, including The French Connection (1971), The Exorcist (1973) and Sorcerer (1977). (And maybe Cruising (1980)? Although, whoa, that's a strange, complicated film, and one of the most arguable films of its (or any) time, which not even I – who am fully willing to embark on an essay connecting a movie to almost literally anything and not really even understand what I'm writing said essay about until four paragraphs from the end – have ever tried to tackle in print.)

By the '80s, Friedkin's career had entered its halting later stages, as did the careers of so many of his wunderkind '70s peers, for reasons that someone sooner or later has to figure out and put in a book so that I can understand. And then he made To Live and Die in L.A., which is in some sense a direct callback to one of the films that made his name (The French Connection) and in another sense is a fine example of a man of the '70s trying to explain the madness of the '80s, and in a third sense offers (along with Cruising, goddamn that film again) perhaps his finest insight into the shadowy inner wilderness of our nation.

To Live and Die in L.A. tells the story of a Secret Service agent named Richard Chance (William Petersen) who is such a loose cannon that he makes other loose cannons looked tied down and stable. This becomes clear in one of the film's early scenes, which shows him jumping off a bridge with a cable tied to his ankle, just to win a bet against his fellow (all male) agents.

The plot of the film revolves around Chance's attempt to catch a counterfeiter named Rick Masters (Willem Dafoe), ostensibly because Masters killed his partner but perhaps more deeply because Masters is a slick bad guy who inhabits the trendy L.A. art scene and always gets away with things.

Chance's new partner is a less experienced, more timid agent named John Vukovich (John Pankow), who wants to stick to the straight and narrow. Sorry, bub, not this time. After their boss at the agency refuses them the money they need to buy fake currency from Masters in a bust, Chance convinces Vukovich that the only option is to rip off a drug dealer to get that money. They do, but the drug dealer gets killed in the process, and then it turns out he wasn't a drug dealer at all but an undercover FBI officer.

While Vukovich falls into a full-blown panic, Chance pushes on, using the stolen money to set up the meeting with Masters. But things go bad here, as well, and Chance gets killed (it's a shocking moment, not just because the erstwhile protagonist in the film gets killed with fifteen minutes left, but also because Friedkin constructs the moment with approximately zero fanfare: one minute Chance is all badass, and then next he gets shot in the face with a shotgun, and that, my friends, is that).

This leaves Vukovich on his own; steeled by the action of the film, he hunts down Masters and kills him. The whole thing ends with an extraordinary coda, in which Vukovich, dressed like Chance instead of his old square self, shows up at the apartment of a woman Chance has been forcing to work as an informant (and to sleep with him) and announces that he's now going to be using the same arrangement.

Rather than repudiating the Chance, in other words, Vukovich has become him.

I certainly hope this doesn't offend your sensibilities, but in order to really make sense of all this, I'm going to have to put you on a nerd bus and take you on a tour of those wild, broken-down neighborhoods inhabited by the hobgoblins of something called "film genre"; don't worry, though, we'll drive fast, keep the windows closed, and won't stop for any suspicious strangers.

To Live and Die in L.A. is an action movie/crime film, descended to us by way of the Western and the film noir.

The Western is perhaps the foundational American film genre, and in its most traditional form concerns the attempt of good guys to keep an expanding society safe by riding around on horses killing outlaws and Indians.

The crime film also represents a strain absolutely central to American storytelling (see Poe's stuff and Hammett/Chandler's repurposing of the British parlor mystery and The Great Gatsby, etc.). It assumes many forms over the years, but in the late 1960s and then the '70s it begins go change.

During those years – under the influence of the social unrest of the '50s and '60s, the violence of the Vietnam war, the unbridled sensibilities of a Hollywood freed from the constraints of the studio system and the Hays Code, and due to a certain cultural cynicism (stagflation, anyone?) – many crime films became increasingly interested in violence and "action" (on-screen thrilling kinetic activity).

In other words, the heroes and plots were infused with cynicism and doubt at the same time that the heroes and bad guys started shooting people more, chasing each other more, blowing more things up, and just generally engaging in more on-screen havoc.

Okay, but how does genre itself play into this? Well, at question in American movies occupied with telling stories about cowboys and crime-solvers is the nature of heroism.

In the Western (traditionally, at least) the hero is heroic because he confronts a bad guy and saves the community. But in the crime film, and particularly the noirs (a series of crime movies from mid-century featuring dark themes and angular lighting, more or less) the hero is not heroic at all but we sympathize with him because he finds himself in an inescapable situation that threatens to (and very often does) kill him.1

There's of course a general storytelling principal at play in this noir approach – Hitchcock observes somewhere that if you see a burglar break into a house you're not going to root for him, but that as soon as you see the glare of cop car lights out the window and realize he's in danger of being arrested, you immediately do start to root for him – but there's also something deeply American.

This is because as central as the White Hat / Black Hat approach of the traditional Western is to the American patterns of thought, it has never quite matched with reality. Part of the allure of the noirs and other crime films was that they pointed out a real, subterranean darkness of the American soul, which is the necessary implication of the violence employed by the heroes of the Western.

Like, what if all of this killing of outlaws and Indians with our blazing six-guns wasn't purely heroic, but represented some need to dominate or some love of violence or something, bro? Did you ever think of that?

And so in the '70s, the decade that produced Friedkin, these two trains of thought finally collided: many films began to marry the heroic structure of the Western (good guy fighting bad guy in an action/adventure narrative) with the moral structure of the noir crime film (a man of impure motives finds himself entangled in an emotional mystery that will lead to his destruction). They were thus revising the vision of the American hero, and got called "revisionist." And, as I said, this occurs at the same time that they're engaging in more and more visual mayhem.

Then comes the '80s.

If there's one single rule that has tended to shape the course of Hollywood history, it's "More is better, let's not be too edgy, and subtlety is for suckers."

Thus a decade which tried to amplify the action elements of the films of the '70s while ditching the moral ambiguity. Essentially, Reagan got elected and people decided they were sick of cynicism and wanted to go back to celebrating wealth and wearing pastels and being cheesy, and so was born – out of the same filmic roots, the Western and the crime film – what we think of as the '80s action film: lighter, frillier, less ethically complicate fare, in which there's a great deal of jocularity involved in killing other human beings.

(Just to give you a sense of the timeline involved here, To Live and Die in L.A. appeared in November of 1985; 48 Hrs. and Conan the Barbarian were released in 1982, Uncommon Valor and Sudden Impact in 1983, Beverly Hills Cop in 1984, Commando and Rambo in 1985, Cobra in 1986, Lethal Weapon, Beverly Hills Cop 2, and Predator in 1987, and finally Die Hard in 1988.)

But it is precisely the hard-edged, cynical '70s vision of heroism and American masculinity that Friedkin seems to want to insist cannot simply be jettisoned.

And through this insistence, he manages to expose the great gaping hole at the center of the American white dude, and by extension America itself.

How exactly does Friedkin do this? I'm glad you asked, because that's been on my mind too. And as I've been watching the world unfold recently and thinking about white dudes and then re-watching To Live and Die in L.A., what has seemed the most important to me is the question of motivation.

One of the things that makes the film so fascinating is that Chance is so clearly ultimately not really motivated by the killing of his partner.

Sure, he's pissed at Masters for doing it, but it's more of an excuse. He does not become a loose cannon or abandon his morals after his partner is killed, in other words; he's this way at the start of the movie. He gets his kicks through adrenaline-charged stunts, and he is already morally compromised and sleeping with the woman he forces to be an informant.

Which is to say that the film is not the story of a man pushed beyond the boundaries by an event in the plot. It is the story of a man without boundaries looking for an opportunity to go further.

This comes to a head in a brief but terrifically decisive moment during the film's really superb car chase (Hell, thought Friedkin, it was a hell of a lot of fun in The French Connection, let's try it again here). This section of the film represents an important pivot point: Chance and Vukovich have just caused the death of the man they will discover is an FBI agent, and are being pursued by his compatriots.

As their car speeds through L.A., we are given a brief flash of what each is thinking. For Vukovich, who's freaking out in the back seat, we get a Peckinpah-esque flash of the body of the recently killed man falling to the dirt: he's trying to come to grips with the fact that he, a Secret Service agent, has just caused the death of a man who did not deserve it.

For Chance, driving the car, we get a flashback to the scene in the opening in which he jumps from the bridge with the cable around his ankle. Note that he does not flash to an image of his dead partner, for whom he is ostensibly doing all this. Instead it is an image of falling into the void, and at the same time doing something macho that his buddies don't think he'll do to win a bet.

This, implies Friedkin, is what's going through Chance's head during the car chase:

Fuck yeah, let's jump off a bridge to show the boys who's got the biggest balls.

Oh my god, I'm falling off of a stable structure down into nothingness.

It doesn't take the brilliance of Sigmund Freud ("Golden Siggie" as his mother called him) to deduce what's going on here: the first (desperately competing with the boys to try to prove you're more masculine than they are) is a rather flimsy cover for the second (being terrified, constantly falling away from safety towards nothingness.)

You will also note that the notion of jumping off a bridge to impress other men ties directly into the underlying psychology of the Western ("Look at me, I'm the baddest man in town and can save the women and the wimps by out-masculining the guys in the black hats"), while the notion of falling terrified into a void ties into the psychology expressed by the noir ("How the hell have I gotten myself into this predicament where there's no solid ground and no meaning and I'm screwed?!")

This is what the film shows us about American white-dude masculinity: American white dudes are obsessed with competition because they don't have anything else in their lives. They feel as though they're falling into a void, and so, to defend themselves from the fear and vulnerability created by that sensation, they call it machoness and convince themselves they're psyched about doing it better than all the other bros.

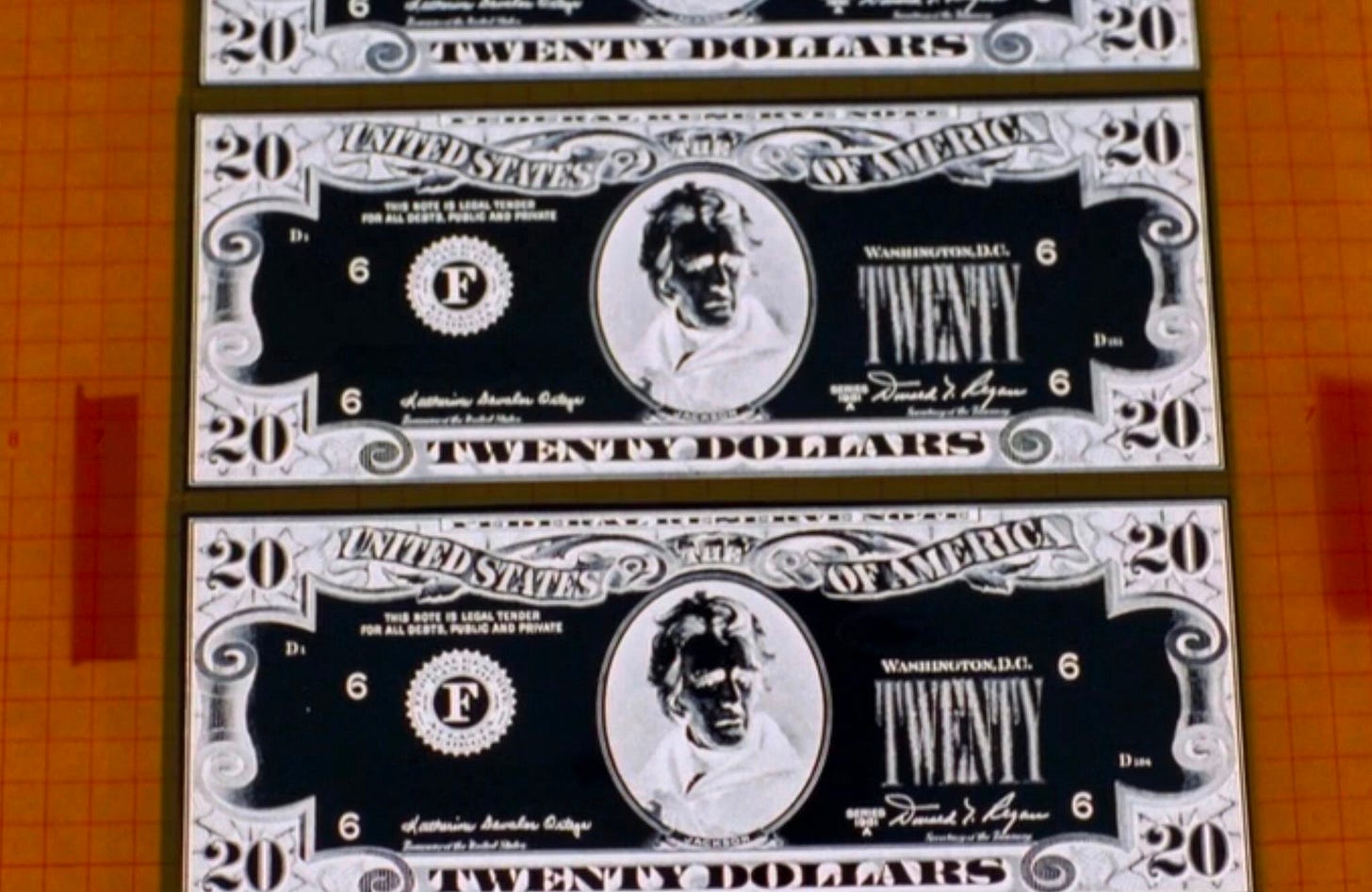

Let's marvel for a moment longer at the narrative construction of this film. Because there's also the character of Masters, the counterfeiter. What does he do?

He makes money. By which I don't mean that he earns it. He simply prints it.

Masters is also a rather avant-garde painter (there's a scene where the actual L.A. painter Mark Gash (credited as himself) explains that he met Masters when he was working with prison inmates in an art program and found him to be quite talented) who burns his own paintings to get his psychic kicks and hangs around in the cool L.A. art scene.

Why do I point this out? Because it goes again to the question of what it is that motivates the Secret Service agent Chance to want to defeat him. Yes, Masters is ruthless and violent, but it's hard to escape the suspicion that his true sin, in Chance's eyes, is doing what Chance wants to do and getting away with it. They are doubles, in a sense, but Masters is just a little bit freer and cooler than Chance.

They both have pale blond women at their beck and call, they both use violence when they need to; yes, Chance steals money when he needs it, but Masters simply prints it. Once this becomes clear, it's hard, again, to avoid the impression that Friedkin is winkingly trying to help us see that what's at stake here isn't revenge for a dead partner or some notion of "enforcing justice" but simply an attempt by Chance to reassure himself that he's more of a man than Masters.

And here we get to the rub, as they say.

You may remember that all those paragraphs ago I began by putting down some thoughts about American sports culture, and my absurd childhood-instilled competitiveness with Texans. You may also remember that what I'm really after today is the question of the deep Americanness of this all.

So where does it come from? Well, obviously, this is a very complicated matter, but I think at least one answer lies in the self-creation of American culture.

You will notice, if you think for much time at all about the history of white dudes in our great nation, that they have spent a great deal of time and energy trying to create a sense of meaning for themselves. Freed in some greater or lesser sense from the history, culture, and traditions of the various "Old Countries," they were set adrift on a new continent and told to just go make it up.

This is devastatingly clear in, say, the history of religion in our country, from Joseph Smith, who invented the American religion of Mormonism, to the Evangelicals, who earnestly believe that America was put on this earth by God to save humanity, because obviously the old European faiths were doing a botched job of it, to the audience for Jordan Peterson's drivel, which involves men trying to find a renewed sense of masculine spirituality.

What is this other than white dudes feeling that they have leapt off of the solid ground and are floating over a void ("If we don't make it up yourselves, we'll have nothing to fall back on!"), and sublimating that fear by declaring that they're the great saviors of everything?

Or take the folks in the 19th Century like Emerson and Thoreau and Whitman. What were they after, if not a new American creation of meaning, through nature and transcendentalism and democracy? And why did we need to create new meaning? Because we had left the old, hidebound meanings behind. We were engaged (or believed we were engaged) in an act of self-creation.

And this, friends, is terrifying.

As Nietzsche once put it:

We have left the land and have embarked. We have burned our bridges behind us – indeed, we have gone farther and destroyed the land behind us. Now. little ship, look out! Beside you is the ocean: to be sure, it does not always roar, and at times it lies spread out like silk and gold and reveries of graciousness. But hours will come when you will realize that it is infinite and that there is nothing more awesome than infinity.

Hopefully, you are now seeing something of what I think is going on here:

The fear induced by being confronted by the need to create our own meaning is one of the keys to understanding the soul of the American. This is because our fear results in a sense of dog-eat-dog competition. If I don't know exactly what meaning there is out there in the world, at least I know I can beat that other guy in some game.

Thus our obsession with sports. Thus my competition with Texans.

A lack of inherent meaning breeds insecurity and status anxiety. A world in which, to borrow from Friedkin, it seems like some folks just get to print money and live a fancy, artsy life, while the rest of us are expected to play by the rules, breeds competitive rage. We do not have ancient cultural rituals to fall back on. We have a capitalistic structure in which the worth of an individual is very much coded as their net worth, one in which we are told again and again, in every area of our lives, that the only way forward is through competition. Through proving that you are better than the other guy because you have defeated him.

And so you get the American white dude.

Now, this raises one final question: what the hell should we do with these guys?

Here's an idea. Like Alfred Hitchcock, Jesus Christ once said something somewhere. The thing I'm thinking about here is how Jesus talked about the way we should treat other people. And I think that his might be good advice to take to heart.

Why? Because in this area – how to treat other human beings – are you really going to try to argue that you have more wisdom than Jesus Christ? I mean, all the religious shenanigans aside, this was a dude who had some fairly profound things to say about life, and if you are just going to ignore his advice out of hand because you think you know better, I would suggest it might be time for a long look in the mirror.

Anyway, I'm pretty sure that some scripture or another Jesus says that we should feel sympathy for people, even the ones we don't like or who are bad to us.

And Donald Trump and J.D. Vance and the rest are, like it or not, human beings. As are the folks who have decided that the most important factor in making a judgement about another person's desire to live a life according to the gender of their own choosing is not actually human compassion or understanding, but the question of which group of uniformed sixteen year olds gets to celebrate at the end of an arbitrarily decided time period of kicking a ball at one another.

The American white dude and his cultural brethren can be profoundly flawed and astoundingly destructive, but they are also made from the same clay – in spiritual, historical, and biological terms – as everyone else.

And Jesus, who I really, earnestly believe has some important things to say, preaches that we should feel sympathy for their condition.

So I do try to feel that sympathy.

But also, you know…fuck them.

As a side note, one of the most interesting ways to understand the noir is as a Western flipped upside down: the West is turned into the City, the noble gunfighter is turned into an often ignoble protagonist, the wholesome frontier woman is turned into the femme fatale…and yet the central questions – of violence and our ability to grapple with the hand of doom – are played out on very similar grounds of theme and action.

Former athlete here (not professionally, not by a long shot, but decades of athletic stuff + personal relationship with several professional athletes): You are 100% correct. I like sports more than you seem to, but before High School, this is a completely made-up issue. In Elementary school I played in co-ed soccer leagues. There are tons of coed leagues for middle schoolers as well. And the only reason I differentiate just the tiniest when it comes to High School/College is because in the US a not insignificant percentage of the population finances their college education through athletic scholarships. Now I happen to believe that trans kids deserve scholarships every bit as much as cis kids do, but at least at this level of sports there are some actual stakes at play (even though the number of trans athletes is so low that in practical terms this is still a complete nonissue for even the most transphobic of parents).

Of course, real issue isn't evil trans kids in sports taking away scholarships from more deserving cis kids, as the incessant media coverage might lead one to believe, but why the hell a person's educational opportunities should have to be incumbent upon their ability to play a sport in the first place.