In the newest Batman flick, The Batman, there's a scene in which our caped crusader (played in this iteration by Robert Pattinson) and his cop buddy James Gordon (Jeffrey Wright) stand in a morgue trying to find clues about what happened to a murder victim. What's interesting to me about the scene isn't the procedural element – the murderer has left a coded clue in a little plastic mouse maze to taunt Batman – but the gravelly whispers in which Batman and Gordon conduct this conversation.

In fact, everyone in the film seems to speak in a gravelly whisper, like high school thespians rehearsing their idea of what Prohibition-era gangsters sound like while trying to keep it down because algebra class is going on next door. But what raises the scene in the morgue from simple trope to high (or low) comedy is that, at its end, a bright-eyed young cop comes down into the morgue to tell our heroes that it's time to go, and he does the gravelly whisper thing too. Is he, like a younger brother, just trying to act like the cool kids? Is there something in the air of Gotham City that attacks the vocal cords? Or is the film simply so desperate to convince us of its gravitas that it cannot imagine having people speak in a different way?

For a couple of days now, I've been struggling to find a mode through which to convey my thoughts about the Batman tale. I thought about making a comparison to the numerous things I enjoy – from alcohol to fast food to the occasional cigarette – that I also don't suppose are good for me. I thought about trying to frame the frisson of portentous feelings these films offer with a quote, perhaps from the theorist Bruno Latour, who commented on "famed power of capitalism for recycling everything aimed at its destruction," or from Brian Dennehy's character in Tommy Boy, who remarked, memorably, "Why say no, when it feels so good to say yes?" I also thought about digging into a bit of etymology, focusing on the word "suspicion" in the title of the piece, and speculating about whether or not that's the right word to describe my relationship with this kind of fare, as opposed to "trepidation" or "wariness" or something else.

But none of those gave me any traction, so I thought I'd just jump right in, grab the bat by the wings, if you will, and try to get right to the heart of the matter. Because I think virtually all of my unease about the Batman story can be located in the way these two men talk to each other in the morgue.

That this dialogue delivery is a betrayal of realism – the way that real people talk in real life – isn't in any way the point. We're talking, after all, about a story in which characters called "Batman" and "Catwoman" dress up in costumes to fight characters called "Riddler" and "Penguin"; in other words, we're in the land of fairy tales. So the fact that everyone talks in an affected way is, in some very real sense, just a part of the ambiance.

The point is, instead, the stultifying insistence of these men's voices – and of the ambiance itself – the way they so frantically try to wrestle us into a certain set of feelings and associations. More precisely, the point is the set of questions raised by this insistence: What are they trying to make us feel? And why?

It's in trying to answer these questions, I think, that we begin to see why the story told by the umpteen Batman films – which in some senses are quite different from one another, and in other senses are all exactly the same – is both so loaded and so telling. It's as good an on-screen indicator as we currently have to the state of American society, and at the same time presents a rather fearsome picture of where we may be headed.

To begin with, step away from the scene of the men with the frogs in their throats and consider the story itself, stripped of the particulars lent to it by any director or actor. This story goes as follows.

Gotham City, where Batman lives, exists in a state of eternal decrepitude and moral degradation. It's a visually dark place, which color scheme seems designed to remind us of (or club us on the head with) the fact that criminality is running amok to the extent that it's virtually in possession of the city. Vandalism reigns supreme, old ladies are getting their purses stolen, people are getting shot in hold-ups, and more, and worse.

There are a few reasons for this, some proximate and others underlying. The proximate ones generally have to do with the fact that the police themselves are both inept and corrupt, and also with the fact that the people of Gotham don't have anyone to save them, for one of the most insistent tropes of the film is that Batman himself has sort of stepped back from his duties and needs to be called out of this somnolent state by a crisis; this calling out is rendered literal in the films by a big spotlight with a bat shape in it that gets shined up onto the clouds, signaling that the times have grown desperate and Batman is needed.

But there's something beyond this, in all of the films. Gotham is afflicted by a kind of malaise. Something has gone wrong, something is going wrong. Somewhere along the line, the good cheer that attends a place like Superman's city of Metropolis seems to have been driven away, leaving Gotham dark and dangerous and degraded.

The cause of this decay is never directly named, but if we pay attention closely enough, we can detect it. And, of course, this being a superhero story (in which the macro-symbolic is insuperable from the character's own arc) the cause is connected to Batman himself, or rather his non-costumed alter ego, Bruce Wayne.

In other words, the origin story of the city as we find it in these films is the same as the origin story of Bruce Wayne himself. That story goes like this:

Once upon a time, there was a kind, benevolent billionaire father figure named Thomas Wayne who was trying to do good in the city. But he was murdered, which is the original trauma that his son Bruce is still wrestling with. In virtually every iteration of the story, we're shown the killing of Thomas Wayne (and, incidentally, Bruce's mother Martha, although she is generally a much blurrier figure) through young Bruce's eyes, so that we experience it along with him.

Thomas's death does two things. First, it leads to his son Bruce being in control of the Wayne billions. Second, it sets the stage – certainly figuratively, and often literally – for the murk into which Gotham has descended. In the sense that his figure looms over the story and the city itself, Thomas Wayne feels like the last good man in Gotham, the last powerful man who had a chance to make the city into a good place. Thus, his death is the event that has led to the fall into darkness with which the city and Batman must grapple.

Given this description, it's fairly easy to see the most basic reason that Batman and his buddy and the rookie cop and everyone else in town talk in a gravelly whisper: it's appropriate, given their surroundings. They live in a crime-ridden city, under the shadow of a great, fallen man.

But this doesn't go quite far enough. Because Thomas Wayne's death also means that this is at heart the story of a boy trying to avenge his father. It's the story of a boy terrified of the world, which in his eyes is filled with dangerous criminals of the sort who would kill the most beloved and important man there is…and then the boy grows up and finds that the world actually conforms with his childhood fears. It's the story of adults, in other words, stuck in a universe defined by the psyches of children.

Often in tales of maturation – and I go to Shane here more than any other film, for it serves as a kind of Ur-text of this sort of story in American cinema, but one could as easily go to Rebel Without a Cause or American Graffiti or Wall St. – what is revealed is the disjunction between the way the world exists to the character before they mature, and the way it exists to them after they mature. It's in the tension between these two states that the story finds its depth.

But in the Batman story, there simply is no maturation. His father has been murdered. The criminals are running wild. The pain and incomprehension of a violently orphaned boy become the materials out of which the universe is constructed.

This is both a juvenile and a dangerous worldview. It's juvenile because, like the kid trained to scream "stranger danger!" at the appearance of any unknown figure, it assigns hard and fast categories to human beings, categories that are absent of either psychological or sociological nuance. What we know is good, what we don't know is evil. The world outside our enclave (or perhaps batcave) is a place of terror, of thugs and evildoers, muggers and rapists.

Another way to understand this is to note that there is not even that most basic and trivial interest in sociological or cultural explanation that underlays other action films. No one, for example, is going to mistake Lethal Weapon or First Blood for intellectual texts, but in both there is at least a hint of the idea that violence in a society is a complex thing, and connected to seismic historical events from which people cannot escape (in both cases, the Vietnam War). Similarly, for all the bitter darkness of movies like The Asphalt Jungle or Kiss Me Deadly or Thief or Reservoir Dogs, there is a sense of society as a place in which there are reasons why people turn out the way they do – some are lucky and some unlucky, some are kind and some are malicious – and of society as interwoven, as connected, as a place of manifold diversity with interlocking, rule-bound systems of interaction which must be navigated.

In Batman's world, this complexity is stripped away. Threat is everywhere, from the crazies in the street to the dark color tones to the gravelly whispers with which everyone communicates. And the flip side of this is, of course, a justification of violence. Because the world is overrun by criminals, vigilante violence is called for.

It really should be pointed out, I think, that the equation the Batman story presents is identical to the one proposed by the authoritarian dictator: I must rule, and with a terrible iron fist, because of the almost insurmountable threats surrounding us. And it should also be pointed out that it bears similarities to the worldview of people in suburban neighborhoods who buy whole arsenals of semi-automatic weapons to protect themselves from the menacing hordes that the cretinous men on their cable news programs are continually screaming about: the world outside the home is chaos and threat and darkness, and so we must arm ourselves.

And thus the solutions proposed by the Batman story. The violent suppression of rapacious criminals is obviously the main one of these. But there are two others lurking in the background.

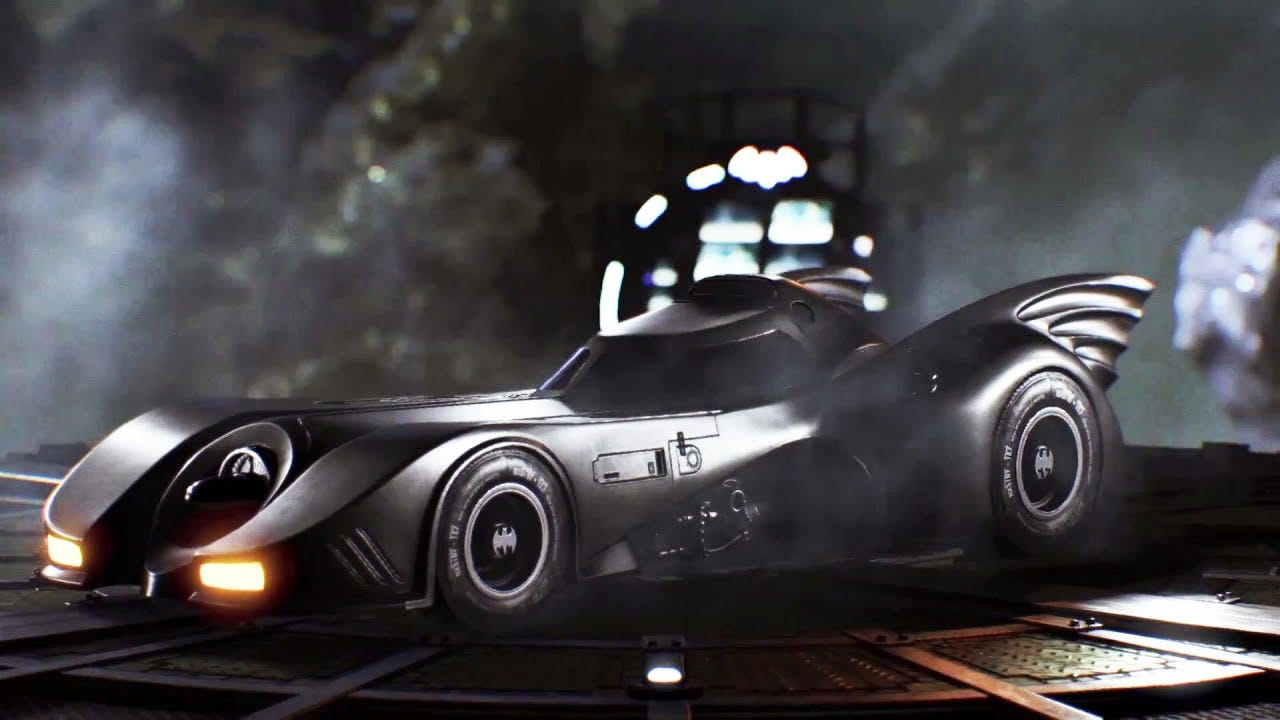

The first is a kind of fetishism of technology, and in particular the technology of violence. The films are full of a kind of pseudo-military hardware, from Batman's battle suit, to the Batmobile – which is presented as a kind of teenage boy's wet dream of a car that is both cool and capable of enormous destructive power – to the contact lenses that are actually cameras that he forces his protégé Catwoman to wear in the latest film, to the various other gadgets and machines that he zooms around in, which perhaps reached their apex in the Christopher Nolan trilogy from fifteen years ago.

Is it somehow an accident that a character played by Morgan Freeman in one of those films gushes about one such lethal toy: "Nothing like a little air superiority!" It's a phrase ripped from military verbiage; are we, watching, supposed to pretend that we don't see in it the winking adulation of that military? Are we supposed to pretend that we don't see the obvious linkage it makes between Batman's armaments – military in nature, but used to keep us safe in our own streets – and the armaments that have flooded America in the past twenty years in the hands of the police, who all across the nation have made it their habit to buy up excess military hardware cast off in the wake of our engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan, beefing up their firepower to insane levels in order to "keep us safe"?

No, no, say the story's fans, waving their hands, don't pay attention to any of that. Batman's world is depraved, desperately in need of a hyper-violent techno-fetishist to keep order, killing off the malcontents one after another because petty criminals are a scourge to "order" and things like due process are luxuries of another age, but you're not supposed to read any comparison to our world into it. Not at all. Despite the fact that this tale is one of the purest embodiments of the totalitarian mindset ever put onto the screen, they cry, it's just entertainment. Despite its seductive Hollywood packaging and the thrill it gives teenagers at the thought of the fantastic, cleansing power of violence, it's just a movie.

And this is not to mention the second solution to what ails the world that the story provides: extreme, orgasmic wealth. For Batman, the story reminds us, again and again, with such frequency that one cannot help but wonder whether this is not somehow more important that the childlike reduction of the universe into predators and vigilantes, is phenomenally wealthy. He is so wealthy that sometimes he even pretends to hate being wealthy, as if he's weary of the burden of all that money, tired of being waited on hand and foot by his poor suffering old butler Pennyworth (note the name, with the diminutive monetary value baked into it), although, the cynic must note, Batman never gets tired enough of the wealth to actually do something radical like give it all away or agitate for higher tax rates on the top one percent.

No, Batman is wealthy. And his father was wealthy. And so at base this is, like most superhero stories in this country, a kind of subterranean, subconscious, barely-pictured-because-we-can't-stand-to-look-at-it, anti-democratic, despairing yearning for a return to monarchy, if not despotism, for salvation by better-than-us, ultra-powerful figures. Things fell to pieces when the last rich guy – Thomas Wayne – was killed by an unruly peasant and the only way order can be restored is for his rich son to stand up and take his rightful place as the guardian of society.

It's a terrifying brew. A view of society not as a site of democratic diversity and engagement, but as a place defined by rapaciousness and fear, in need of an iron hand to control it. A fetishization of the technological violence of that means of control. And an assurance that that violent control is most necessary, and can be most trusted, when it's wielded by the richest among us.

That the vital importance of these things is not immediately obvious to an American audience is the ultimate reason, I think, for the story's continual over-insistence on them. There is still, in our country, a strange, deep, strong democratic sentiment. It can be found fitfully displayed in our comedy, our literature, our art, our cinematic history. There is an innate resistance to the world-view of the Batman story, with its adulation of top-down, violently imposed order. And it's this resistance that must be overwhelmed by the story's repetition and exaggeration, by the intimation that its totalitarian tendencies are actually gravitas.

In the end, this is, the scaffolding that leads to the fact that the characters must, at all times, converse in gravelly whispers. Not even the spoken voice can be allowed to betray the formal, quasi-religious incantation of the whole. So Batman and his buddy, standing in the morgue, trying to figure out the clues to a murder, must do so in voices precisely pitched to scare the rest of us into submission.

Am I making too much of all of this? Perhaps. We are adults, and able to distinguish between movies and the world. We can enjoy them in the theaters, or in our easy chairs on a Sunday afternoon on television, without being turned into vigilantes. These films are just a way to spend a few hours of our time, diverted by the fisticuffs. They are just beloved comic books from childhood put up there on the screen for us to enjoy. Perhaps this tale bears no relation at all to the contemporary currents of American life, and perhaps there will be no transference of this story into the nooks and crannies of the consciousness of the people who flock to see it. God knows I've seen just about every iteration of it myself, and I'm still living to tell the tale.

But I'm suspicious of it just the same.

Enjoy this piece? If you want to support me, please share tylersage.substack.com with anyone you know who's interested in film, culture, or ideas. And please consider subscribing for $5 a month: you'll receive every piece in full, get full access to the archives of this site, and greatly contribute to my ability to keep writing.

If you'd like to read more of my work, my book on William Klein's cult classic superhero film "Mr. Freedom" is now available in the Constellations series (Auteur/Liverpool University Press). Read an excerpt from the introduction here.

If you'd like to buy a copy of the book, you can buy it here https://global.oup.com/academic/product/mr-freedom-9781800856943?lang=en&cc=us.

Sublime, thank you.