This is the second of a series of essays on film and the upcoming election in America. You can find the first entry here. As always, thanks for reading, and if you have observations/disputations/suggestions, feel free to hop into the comments section below.

At the end of my last rumination, I suggested that I might spend some time in this series thinking about, from the perspective of American film, one of the most important political questions of our time: why is it that the MAGA movement and Donald Trump have attracted such a fervent following?

There is, obviously, no one answer to this question. I think it's incumbent on all of us to grant other people the same degree of complexity as we would like to be granted. Put differently, reductionist answers – eg. "It's because of race! They're all scared of minorities!" – should be trusted only to the extent that you are willing to have your own entire belief set reduced to a single factor by people with whom you disagree.

Put differently again, people who disagree with you are not somehow made simple because of that disagreement, and it's intellectually bankrupt to treat them as though they are.

Having said that, I'm not writing a book on sociology, history, and whatever else will ultimately go into the work of seriously answering the question of Trump's popularity. Nor am I educated enough to do so. There's necessarily going to be some reductionism in a blog post put together in a coffee shop on Sunset Boulevard on a few mornings in September.

So here's one idea about one thing that has made Trump and the MAGA faction so appealing to so many people: the modern world.

What the hell does that even mean, "the modern world"?

I'm glad you asked. But before I talk about how movies help us understand this, I'm going to answer with an idea articulated by the writer who has probably influenced my own thinking about film criticism more than any other, the art historian T.J. Clark. (Whom I've referenced before on this site, both explicitly and implicitly.)

Clark has spent a good deal his extraordinary career trying to understand what the painters and paintings that constitute the turn to Modernism – very, very roughly, the period consisting of the shift from the older, agrarian world of the 17th, 18th, and 19th Centuries to the modern, industrial world of the 20th Century – can tell us about the experience of going through that transition. In the course of this exploration, he has necessarily also thought about what it is, exactly, that "Modernism" or "the Modern" consists of.

Clark has worked his ideas out over the span of some fifty years now, including books on Picasso, Manet, Cezanne, and religious painting, so there's no way for me to summarize them here. But I will borrow one that has stuck with me for a long time, which he laid out in his 1999 masterpiece Farewell to an Idea.

This is the notion that one of the signal attributes of the shift from the older world to the modern one is that the new, contemporary, industrial, urban experience that came crashing down around us sometime at the end of the 19th Century was marked by a signal elements: contingency.

By this word, Clark signals the idea that the modern world is essentially unpredictable. Existence in it is contingent on factors that are far larger than we are, and often feel far larger than we can comprehend.

This is a huge difference from the way life was experienced for people before modernity. For example, instead of the orderly progress of the seasons determining our lives – when to plant, when to harvest – and instead of living in communities the scale of which we are able to comprehend, people who lived through the massive shift to the modern world found themselves at the mercy of things like global markets, price fluctuations driven by evens in places on the other side of the globe, and factory wages as determined by the strangling invisible hands of supply and demand.

One of the primary effects of this is to make people feel more exposed to risk, in every part of their lives. The technological and cultural upheavals that attended the Industrial Revolution, the galloping inventions of modern technology and science, and the rapid advancement of machines of warfare, the swings of stock markets, the vagaries of urban employment and unemployment, the sudden influx of masses of people into cities;– all of this created an experience of life in which chance played a much greater part than it had before. Life became less stable, more exposed.

For Clark, this is a part of the context in which we should try to understand the several revolutions of painting that began sometime in the late 19th Century.

My argument is that we have been living in an analogous moment of our own as the 20th Century has moves into the 21st, and that this is written clearly not in our paintings but in our movies. To be clear, I'm not going to argue that this is the only way to read the last few decades of the history of our cinema, simply that it's one way to understand them.

And it helps lay bare something about the way we live now.

Many ideas have been advanced, including by me, to explain the peculiar tone of American cinema during the 1970s.

The nation had just been through a serious of shattering upheavals. The Vietnam War was staggering into its final years. The '60s had seen the Civil Rights Movement, along with the women's and gay liberation movements. But the tone of the decade of the '70s in American film – inasmuch as that's a thing that can be articulated – is something darker, something far more bleak, than something one might expect from a country in these circumstances.

"Cynical" is a word that is often used to describe these films (and, again, one I've used myself) but I'm no longer sure this is quite right.

In the story told by Taxi Driver (1976), surely one of the decade's most representative films, what ails Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) is a kind of apocalyptic alienation. There is a distance, at the same time, between the world as he would like it to be and the world as it is, and between himself and the world of goodness, normalcy. He sees the streets as being full of human trash that he yearns to heroically clean up; at the same time, he cannot connect with the people living the somewhat plasticized lives of ordinary, traditional Americans that he encounters in the form of workers for a political campaign, and one woman in particular (Cybill Shepherd).

There is something, in Bickle's eyes, too false, too shiny, too insincere in these people. The world is somehow not working right, even though they believe it is.

A similar feeling runs through a large number of films from the decade, from Coppola's The Conversation (1974) to Schrader's American Gigolo (1980), from Pakula's "Paranoia Trilogy" to the variegated films that represent the birth of modern horror, from war films like M*A*S*H (1970) to Westerns like Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973).

The longer I've thought about it, the more I've begun to think that the particular sense of existing in the world embodied by these movies, taken as a group, does not simply represent a reaction to Vietnam or the Watergate-era revelations about the U.S. government. It also represents the first whispers of an awareness of a changing world. One that was shifting – due to changes in technology, the economic structure of the globe, a newfound awareness of environmental peril, and many other factors – from a place that had seemed stolid and predictable to a place that was dominated by contingency.

This last may seem like a ridiculous statement, given that the previous half-century or so before the 1970s had included two World Wars, the Great Depression, the Holocaust, and the advent of nuclear technology, but it is one of the most central facts of history that it doesn't always quite make sense. Because in America, the triumph in those World Wars, the overcoming of the Depression, and the success of mid-century economic policy had created a sensation of vertiginous uplift, a feeling that the American ascent might continue forever.

But it would not.

I know I promised there would be no math in this space, but here are a couple of interesting charts in terms of film history. The first is Thomas Piketty's famous one that shows the percentage of the nation's income taken home by the top ten percent of wealthiest Americans over the last century.

What this shows is that early in the 20th Century, folks in the top 10% were capturing almost 50% of the nation's income. Then, in the middle of the century, that number dropped, and for a couple of decades they were only capturing in the range of 30% to 35%. As the century drew to a close, however, thing started to change. There was a slow rise between 1960 and 1970, a bit of a plateau during the early '70s, and then an extraordinarily rapid rise starting in the late '70s. (This trend of the wealthy taking home more and more of the national income has continued, incidentally (or not), in the decade and a half since the end of this chart.)

For our purposes, though, the point is that there is a clear moment when inequality in this country began to explode after a period of relative stability, and that moment is the 1970s.

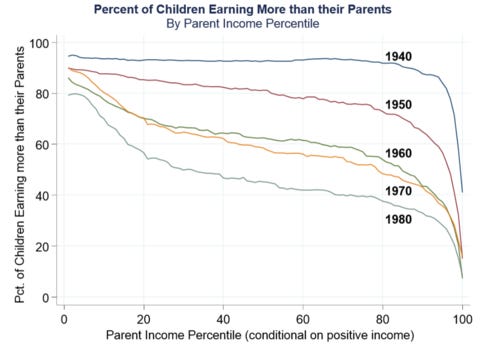

Just for fun, and this is the last one, I promise, let's look at another chart. This is from a paper called "The Fading American Dream" released by a team of economists led by Raj Chetty.

What it shows is that if you were born in 1940 or thereabouts, and if your parents were in the bottom 90% or so of earners in America, you were almost guaranteed to earn more than they did (adjusted for inflation). But with each passing decade, your chance of earning more than your parents has decreased, until, if you were born in 1980, you are more likely to earn less than your parents than you are to earn more.

I would also note that, as with Piketty's graph above, this is a trend that is continuing to worsen.

In America, social mobility – the ability for people to improve their lives economically in relation to the lives of their parents – has completely stalled out. It is now a relatively foreign concept in the lived experience of most people. And you will notice that the first generations this began to happen to were the ones born in the '50s and '60s – the ones, in other words, who were in their teens and 20s during the 1970s.

I will not force you to grind your eyeballs over any more facts and figures, but I will note that a great deal of data – from wage growth to home ownership – shows a similar trend line as we plunged towards and then into the 21st Century. We have steadily moved towards a new life, a different life, and not necessarily a better one.

This is not just a matter of economics. Ever since the publication of Robert Putnam's Bowling Alone in 2000, people have been increasingly aware of the degree to which our social lives – as measured by membership in social clubs, church attendance, participation in civic events, hell, just the amount of time spent in one another's company – have steadily withered away in this country.

All of which is to say that we have been living through an era of radical change, an era of a new Modernity once again, one in which we are socially atomized and in which our economic lives have reached a new level of dependency on events beyond anyone's ability to control.

Is all of this responsible for the tone of 1970s cinema in America? Perhaps not directly. But people go to movies to see what they're feeling, and to feel what they're seeing, and to argue that there's no connection strikes me as a misguided attempt to put a great deal of faith in coincidence.

Which brings us to the 1980s.

Famously, this was a rather sunny decade in American cinema. And in the main, this is for obvious reasons. Audiences grew tired of the bleak vision of the previous decade, Reagan promised renewal, and a kind of pastel-colored, sweater-around-the-shoulders euphoria filled the air.

But, to return to Clark's idea, beneath this jubilee, I think you can clearly see the stark outlines of the continuing emergence of that marker of epochal change: contingency.

Here's a question to put this into focus: if we try to sum it up in a metaphor, does the decade of the '80s in cinema feel more like walking into a jubilant casino, or a staid bank? Both can make you money, of course – and the feeling of money was one of the things that drove the 1980s – but they do it in different ways. The casino by tempting you to wager, the bank by putting your dollars to work.

I think the '80s on screen feel like a casino. There is a certain garishness to the decade, a showiness, flashing neon lights and huge grins at the possibility of a big score. . . all hiding a whiff of despair.

The cinema of the '80s is not like that of '50s, with its elegance, its predilection for the suave, its boots-on-the-ground protagonists. Instead, the cinematic world of the '80s is oversized, over-advertised, almost cartoonish in its eagerness. Take, for example, the decade's single greatest on-screen symbol for economic success itself: the world of high finance.

In movie after movie from the '80s, the men (almost always) who represent what it means to "make it" are stockbrokers, executives, corporate attorneys. They are flashy and swashbuckling. From Trading Places (1983 )to Wall Street (1987), from Risky Business (1983) to The Secret of My Success (1987) and Rain Man (1988), winning economically in the '80s is presented as a kind of speculative adventure, a cross between a roulette game and a three-card-monte hustle.

This is not a world of working hard and doing better than your parents did. It's a world of massive success and titanic failure, of financial rollercoasters zooming up and down with people scream wildly in exultation while they try not to fall off.

It's a world, in other words, dominated by risk.

Whole other swaths '80s film history evince a similar set of hopes and anxieties.

Consider one of the other signal elements of the decade: the Spielbergian impulse to reassure the audience. For all the talk about how Spielberg feels the need to re-construct the nuclear family in his films, perhaps even more pronounced is his need to tenderly embrace the audience and assure them that it's all going to be alright in the end. And it's a need that pervaded the decade, not just in his films, but also in the films of the directors he influenced.

The child-like feeling of wonder that infuses films like Raiders of the Lost Arc (1981), E.T. (1982), Ghostbusters (1984), The Goonies (1985), Back to the Future (1985) is there for all to see, but the question that goes too often unasked about these films is that of the need in the audience they satisfied. Why did these people respond so strongly to movies that evoked the sensation of being a child?

One obvious possibility is that audiences were looking for the consolation and escape offered by films that brushed aside more adult concerns in favor of a youthful, worry-free space.

Because one way to deal with anxiety is to hide from it.

Under this reading, the unease that fueled so many films in the '70s never really dissipated; it was, instead, simply driven underground in a kind of desperate attempt at cultural compensation.

Think of the neo-noirs, like the remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice (1981) and Body Heat (1981), which transformed into the erotic thrillers – Fatal Attraction (1987), Basic Instinct (1992), Indecent Proposal (1993), etc. – that would dominate the end of the decade and the beginning of the '90s. In these films, even dating and sex has become contingent, risky, an arena in which your paramour might flip out, betray you, or kill you with an ice pick.

This cycle of films suggests that even the midst of the Reagan romanticization, the anxiety of the modern was still present, if lying just below eye level.

In certain movies, like Lynch's Blue Velvet (1986), Verhoeven's RoboCop (1987) or Cox's Repo Man (1984), this anxiety became the main thematic focal point. For certain directors, like John Carpenter (The Fog (1980), Escape From New York (1981), They Live (1988)) and Larry Cohen (Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), The Stuff (1985)), the question of the terrifying underbelly of the mainstream became virtually the main preoccupation of their output in the decade. For still others, like Joe Dante, the best way to suggest it was by making films that operated just a few crucial degrees off the Spielbergian axis (Gremlins (1984), The 'Burbs (1989)).

But this anxiety also rears its head in places you might not expect. For all of its wisecracking perfection, there's an inescapable suggestion in Beverly Hills Cop (1984) that the plasticized wealth and harmony of '80s America is a mirage, as fake as a Hollywood boob job, and that the reality of the country is Axel Foley's much grittier Detroit, land of cigarette thieves and murders in blue-collar apartments. And what are Tootsie (1982) and Dead Poets Society (1989) if not, in part at least, parables about the madness and risks that attend trying to break through to the top in this new America?

It's an overstatement, and an over-reduction, to say that as the '80s rolled over into the '90s, the anxiety of the modern moved to the center of our filmmaking. But I think there is more than a kernel of truth in this idea.

There is the indy cinema of disillusionment created by directors like Richard Linklater and Gus Van Sant. There are Quentin Tarantino's fables of a cool pulp grittiness that yearn for an era before things got so sleek and false and at the same time seem to argue that everything new is simply something old repackaged. There are Wes Anderson and P.T. Anderson hungering (in different but oddly complementary ways) for a return to the human, grasping for an emotionally truer existence where the painful truth of things can be laid bare. Everywhere one looks in the decade, there are filmmakers articulating a sense that something is misaligned down there in the tectonics of our society.

It was as if the world had let them down, and so the world's grasp on them must be rejected in favor of…something else. What that something something else actually was, remained, in classic Gen-X style, elusive, but a sense of it pervades their work. There is in all of these directors something of the battle cry of the New Hollywood of the late 1960s and early '70s, but with a baked-in awareness that the world has already strayed from its orbit, the bounds loosed, and so it's not much good even hoping for hope, despite the fact that we always do.

If all that sounds too abstract, consider that the '90s is also the decade when the disaster movie makes a roaring comeback, as if there was something in the audience that not just wanted, but explicitly needed to be swept up in tales of the entire world under threat.

Independence Day (1996) puts this threat into the form of aliens, Armageddon (1998) and Deep Impact (1998) envision it as a meteor hurtling towards the earth. Some of this seems to be tied to the first glimmerings of public consciousness of climate change – Twister (1996), Volcano (1997), Dante's Peak (1997), for example, all tell variations of the story of the earth itself turning against humans – but it should be noted that awareness of environmental degradation played out in an entire cycle of nature-horror films beginning in the 1970s (I'm thinking of things like Frogs (1972), Night of the Lepus (1972), Phase IV (1974), The Swarm (1978) and even Silent Running (1972)) and never really stopped.

Climate change is to our Modernity what factory pollution was to the early 20th Century's.

The '90s also produced a number of fascinating threat/nostalgia films, like Schindler's List (1993) and Saving Private Ryan (1998) (the history of contemporary American film is ineradicably tied to Spielberg) in which the audience is at once terrified by the enormity of a disaster and thrilled by an older generation's ability to overcome it. It seems clear that at least one way to read these films is as raising, at least implicitly, the question of our own ability to overcome similar challenges.

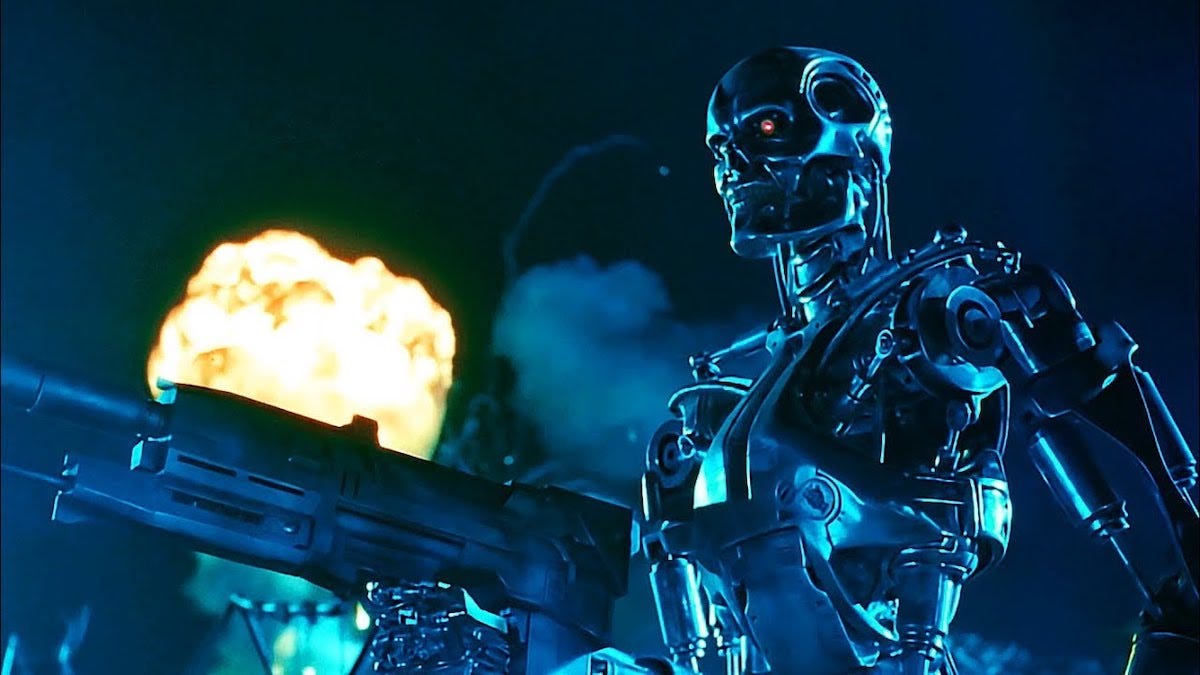

All of which is not to mention the terrible technological anxiety the decade brought into focus. Terminator 2 (1991), as did it predecessor, asks the question about what will happen when the machines we've created decide to destroy us. Movies like The Net (1995), Johnny Mnemonic ( 1995) and Enemy of the State (1998) move the thriller into the newly opened domain of the internet. Even You've Got Mail (1998) provides a template for the intrusion of the internet into the world of the romantic comedy.

Finally, the box-office destroying films that closed the decade have a distinctly anxiety-ridden tone. The Matrix (1999), although now commonly (and not unjustly) read as a kind of exploration of the trans experience, is perhaps more directly read as a paranoia film about the new technology that's overwhelming us. And even Titanic (1997) – maybe not surprisingly, given the fact that its director birthed the Terminator saga – is about a massive ship carrying a load of humans who think they're completely safe, only to find that an inevitable and inescapable danger is going to sink their craft and kill them all.

These trends have continued on into the '00s, perhaps even strengthening on the back of younger Americans' sense of having arrived at a particularly fraught moment in history.

The super-hero movie cycle is, for my money, Exhibit A in this regard, combining as it does the childish sense of reassurance of the early '80s, a continuing psychological terror at the apocalyptic size of the things assailing us, and a culturally queasy-making desire for someone, anyone, with an outsized amount of power to save us.

But there's also the regular-guy-who's-a-secret-badass tale that has come to dominate the action genre, in the form of everything from the Liam Neeson Tough Guy Renaissance to the John Wick franchise to the films from The Guest (2014) to Nobody (2021) that serve as action vehicles for actors not previously seen in that light. This narrative radiates an almost paranoid sense (recalling the Bronson flicks of the '70s) that regular people are under drastic threat, which it assuages by allowing the audience the psychologically-revealing relief of hollering (hopefully inside their heads) "You messed with the wrong guy!"

The fantasy here is, of course, that we might actually be that secret badass, able to conquer this threat through an almost magical set of violent capabilities. Or at least that we might be protected by him.

And although it makes sense to see the reboot and sequel mania that has had the industry in a death grip for several decades now as being driven purely by corporate financial concerns – because no matter what kind of dreck they throw on the screens, if it extends a story audiences already know, it's guaranteed a baseline audience – the stalling-out of creative film culture also seems to have a great deal to do with a society trying to dig in its heals and desperately look backwards for some kind of stability.

In all of this, there is the same strong current of fear and anxiety that has run through our cinematic history now for decades. It has strengthened and weakened at times, and taken different forms on the screen over the years, but during the last half century we have never been without the feeling that the world is rushing forward just faster than we can keep up with it, into a continually new era in which each moment will be just a bit trickier to navigate than the one that came before. This is contingency writ large on the silver screen.

Let me note two final things about this story of cinema I've just told.

First, as I stated above, I am not claiming the above to be the history of recent movies, so much as it is one history of them. There are many other fascinating and worthwhile ways to understand the continuing evolutions, or lack thereof, of our film.

Nor am I arguing that this is a fundamentally dour or apocalyptic history. There are as many joyous films as pessimistic ones in the time I've been discussing. But I do think that at least one of the main topics of our cinema, for decades now, has been the sense of a radically an unavoidably changing world, one in which we are subject to the dominion of increasingly large forces, and in which life itself is a gamble, in every sense.

And all of this helps us understand a great deal about the candidacy of Donald Trump.

How?

The simplest thing cinematic history allows us to see, I think, is the reason for the primacy of fear in Donald Trump's appeal. People are anxious about the large-scale historical changes we're experiencing. They have been for a long time. This has been reflected back to them in their culture, but for the most part, politicians have tried to deal with it like adults.

And then along comes a childish man who rings as many imaginary alarm bells as he can find and tells folks that they're right to be anxious, that, in fact, they probably aren't anxious enough, because existence is even more terrifying than their inchoate sense of it has led them to believe. And it works, because fear is a prime motivator for human beings.

Simple enough.

But more deeply, this history can help us understand the reasons and ways in which Trump – who has an almost barometric ability to sense and articulate grievance – has adopted the specific rhetoric and set of issues he has.

An initial way to approach this is to think about how the worldview that Trump foists onto his followers differs from that of the more traditional Republicans of the last half century. There is no room in Trump's fervid imagination for the notion of American world leadership that animated men like Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush. I will sidestep, for my purposes here, the question of the moral qualities of these men and their decisions, and instead note simply that they believed that the challenges facing the country required a certain kind of aggressive, forward- and outward-looking policy.

In marked contrast, Trump has succeeded by inundating us with a terrified rhetoric claiming that if we are to survive as a nation, we must adopt a Fortress America approach to the outside world. Cut off immigration, abandon NATO and our other alliances, raise tariffs sky-high, etc.

What Trump pitches, in other words, is the idea of a nation under siege. A nation that has no choice but to retreat into a shell if it does not want to be overwhelmed by the rising tide of international threat.

But the secret of this stance is that it is not really about foreign policy at all.

There is no real, serious economic support for Trump's claims about tariffs – everyone knows that the price increases incurred by these will simply be passed on to American consumers rather than borne by folks in other countries. Nor is there any real thought behind his isolationist, align-ourselves-with-the-dictators-of-the-world approach to diplomacy, which would clearly result in further destabilization of both American power and international affairs.

These are not ideas, in other words, that emerge from a plan of what we should actually do in the world.

They are ideas (a word admittedly being stretched almost past coherence here) that arise from Trump's uncanny ability to put into language the undercurrent of anxiety plaguing us. They are not policy, but psychology. They do not have anything to do with actual, rationally-thought-out governing principles; they are glittering slogans thrown out to at the same time exacerbate and ameliorate our sense that there is a looming thing out there threatening us.

The world is unstable, uncertain, contingent; what was can no longer be trusted to be what is. And what should we do? Wall ourselves off from it as best we can.

Here are the financial anxieties represented by the '80s cinematic stockbroker, the sense of foreign economic invasion that lurks behind something like Die Hard (1988), the insidious threats hinted at by the technological-anxiety films – all rolled into one. It's out there, you've seen it in the movies, and if we don't hide from it, it's going to gobble us up entirely.

To take a specific example, it's remarkable how closely Trump's rhetoric resembles the sense of America presented in something like Carpenter's Escape From New York, in which the entire island of Manhattan has been turned into a free-for-all maximum security prison, into which our hero must journey to save America from its own nuclear folly. For Carpenter, this is a satire, a way of mocking the Reagan era's insipid self-congratulation and of suggesting that the end result of the idiocy of the ruling class is horrific conditions for the dispossessed. And for Carpenter (as for nearly any artist worth their salt), the point isn't to whip up the audience by assuring them that they're right when they fetishize American power; it's to challenge them, to force them to rethink their adulation of that power.

For Trump, the same vision is put to opposite ends. He does not use his fever dream of a collapsing America to challenge his audience to think differently, or in a more moral way; he strokes their sense of grievance, offers them easy choices and convenient scapegoats. He plays on the negative response, the feeling of the in-group, the mocking slogan.

He is, in this sense, a naked propagandist.

Trump's use of his favorite topic, immigration, operates in exactly the same way, and also has nothing at all to do with the realities of the actual world.

In a very real sense, immigration is about numbers, policy, and human beings. What kind of bureaucracy has to be set up do deal with the fact that vast numbers of people are making the decision to try to improve their lives by coming to our country? How many of them can be accommodated, and at what pace?

And are the kinds of people who would decide to risk their lives by trekking thousands of miles in horrendous conditions in order for a shot at a better future – you will note, if you are historically minded, an interesting parallel between a South American voyaging north in search of their future and a pioneer of two hundred years ago voyaging west across the plains of America to do precisely the same thing – are the kind of folks who would risk life and limb in this way for self-improvement exactly the kind of folks we should want as part of our citizenry? Or maybe not?

For Trump, however, this issue is not about human beings or numbers or the fact that immigration has been a constant in American life since the founding. It is a stand-in for the darker fear assailing us: the changing world.

He has no interest in it as an actual problem that might be treated with the kind of (to him) boring policy decisions our government has been making for several hundred years. Instead, it is simply another ray-gun of fear to turn on his followers.

The truth is that things are less stable than they once were. We are living in a new economic modality, one in which we are exposed to vertiginous risk, in which upward mobility is a fading dream. But it is these difficulties, not the reality of the challenges America faces with its border, that Trump is playing on when he rants about immigrants. He senses, channeling some dark current of energy from the underworld of our psyche, the psychological toll that changing economic realities have taken on Americans. Then he puts the Halloween mask of immigration onto those fears.

Travis Bickle's '70s anxiety about the scum flooding the streets, the American auto workers dealing with an encroaching Japanese company in Gung Ho (1986), the noble humans fighting against an alien invasion in Independence Day, the superheroes doing the same thing in the endless iterations of the Marvel universe films;– we have been manifesting our economic anxiety in the form of invasion narratives for a long time.

Trump's reptile brain understands this, and understands how to turn it from a political issue into an existential one in which we're at threat of being raped and pillaged and having our pets eaten by the aliens pouring at us from every direction.

And after playing these fears like the Devil plays on his fiddle, what is the offer Trump makes us?

It is strongman's offer. Ignore the terrible things I've done, because I'm the only one who can save you. Or, more precisely, the terrible things I've done – from raping women to ripping off everyone in sight to trying to tear down our democracy – are evidence that I'm strong, and thus the very reason you should support me.

The despot's playbook is, and always has been, pretty simple: first, he blows the embers of fear into a conflagration, and then he presents himself as the only person who can put out the fire. As I argued in my previous essay, in Trump's hands this becomes a kind of twisted take on the traditional American heroic narrative, one that adopts its trappings while abandoning its ethical and historical framework.

But it is his most famous claim that reveals how deeply Trump has managed to leverage the contingency of our modern era against the country he is running to lead: he will Make America Great Again.

What does this actually mean?

It is, in part, an attempt to summon the hoary phantoms of Manifest Destiny and the American Dream and all the rest of the mythos of America, and to claim that those phantoms are on his side.

More directly, though, it's a promise to return us to a moment before the contingency of the modern world began to feel overwhelming. It's an almost Spielbergian attempt to take his audience in his arms and assure them that it will be alright in the end, because he will make it alright.

Like Travis Bickle, Trump will clean up the scum. Like Marty McFly in Back to the Future, Trump will return to the past as a way of improving the present. Like the corporate nostalgia peddlers drowning us in their reboots, Trump will wrap us in a warm fluffy sense that things used to be better, and if we just close our eyes and wish away the noxious fumes of reality, we will, for a few moments at least, be safe in our entertainment.

In the end, the fantasy on offer from Donald Trump is the childish fantasy of gaining power by giving power to the bad man who promises to be nice to you. It plays on a remarkably canny sense of the average American's anxiety about the course of history in the past half-century, but it is no more based in reality than is Captain America's attempt to deal with a horde of galactic invaders by bashing them with a magical shield.

Both are fantasies, and both reveal something about us and our times.

But only one includes the actual responsibility for the lives of hundreds of millions of real people.