Like many of you, I'm trying to think through, in real time, the catastrophe occurring in American politics.

Since the inception of this site in 2020, I've seen it as a space to offer not fully worked-out essays or perfectly unified theories but simply ideas as they occur to me. I find thinking pleasurable, and I find it pleasurable when others allow me to trace the course of their thoughts, and so I thought that's what I'd do in this space: think out loud.

Because the course of my career has taken me to Hollywood, and I was at that moment in the process of writing a book about a movie, I called the site "Thoughts Mostly on Film."

I mention this by way of acknowledging the fact that I have not, recently, been writing about film at all, but also as a kind of reminder that we all have different frames of knowledge and experience that we bring to what we are experiencing right now, which is clearly one of the greatest inflection points in American history.

The people who are leading the war of ideas on the side that needs to win if America as we know it is going to survive operate in this way. Paul Krugman is an economist. Harry Litman served as a U.S. Attorney and Deputy Attorney General. Tim Miller worked in communications for various Republicans. Heather Cox Richardson and Timothy Snyder are historians.

In my own way I'm trying to bring a different field to bear, for I've spent my life making, thinking about, and teaching others about art.

Which is why the following question has been on my mind: What good are American movies in a time like this?

I think the answer is that they are foundationally good.

One of the most fascinating things about Hollywood is the disjunction between the way people in this town act and the things they put on the screen.

It's not an uncommon in Hollywood to remark, with a wry grin, that the next truthful person you meet will be the first. Everyone is on their hustle, trying to land or launch the next project that will make their tinselly dreams come true, and because of that, everyone exaggerates and prevaricates.

People are constantly telling you in dead earnest that they're about to have financing for their new project in place, or that they're just around the corner from being able to finance your new project; they're constantly dropping casual comments about how they have Aaron Eckhart or Kristen Stewart attached to a script, or that a guy they know at Blumhouse or Plan B flipped out over their movie idea and it's getting greenlit in the next couple weeks.

The cardinal rule out here is that you say yes to everything, whether or not that's the real answer.

Can you write comedy? Absolutely. Can you write a family drama that reads like a cross between Aaron Sorkin and Sam Shepard? Absolutely. Can you tap dance in this scene if we need you to? Absolutely. Do you know how to use Adobe Premiere Pro to edit? Absolutely. Can you handle the logistics for a twenty-two day shoot in Thailand that involves travel, lodging, and food for upwards of a hundred people? Absolutely. Do you have any experience handling firearms? Absolutely.

Because the fantasies of making it so vastly outstrip the opportunities to actually do so, and because so much success out here is based on blind, dumb, capricious, nakedly unfair luck, you learn quickly to tell people you can do anything (on the off chance that something actually comes through) and that you're also right in the middle of a meteoric rise (on the off chance that someone will be impressed and give you the chance to actually work on a project that will allow you that rise).

And this is not to mention all of the betrayal and treachery and double-dealing that come with the fact that in Hollywood – as in any industry where there's a great deal of money at stake – people are often faced with the choice of "making it big," or staying truthful to their word or their friendship or their integrity. They frequently choose the former.

This is not to say that there are not good, earnest, honest, decent, smart, funny people in Hollywood. The town is swimming with them.

But it is to say that the pressures of the industry we're engaged in often lead us to relegate truth and honesty to lesser positions than dreams and ambition.

This, however, isn't the interesting thing.

The interesting thing is that this city, despite its devotion to tendentious half-truth and its long tradition of becoming successful by pushing the faces of your friends and competitors in the mud, makes something – movies – that are focused almost entirely on morality.

Put differently, there is no institution in our culture that is more obsessed with exploring what it means to live a moral life than is the American cinema.

If you don't believe me, let's think through some examples.

Is there a movie more beloved by man-bros than The Godfather (1972)? They love the whole thing – the violence, the funny line about the cannoli, the horse's head in the bed, all of it – and they should, because it's a great film. But what's it about? A decent kid, Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) who out of familial loyalty falls into the darkness and violence of being a crime boss.

At base, it's a story almost entirely about morality, a tale of the corruption of a single human soul. Is it a cautionary tale? Perhaps. A warning? Perhaps. A sociological indictment? A kind of subterranean history? Perhaps.

What exactly it "means" is open to some level of debate. Because, like nearly every movie, while it focuses on the question of how to live and act, it is not a "lesson" of some sort. It is a story, from which we may take what we may.

This last bit is important.

My sense that if Donald Trump were ever to be strapped to a chair and forced to watch The Godfather (for he clearly doesn't have the attention span to sit through a movie, let alone a national security briefing) he and I would say it was about very different things. He, for instance, might say that it's a heroic story of a young man finding success in the great free enterprise system of America, and that the thing to take from the film is that we should lower that young man's taxes and perhaps put him in charge of an invented government "agency" tasked with demolishing the government so that folks like Trump and him can prosper even more.

I might read it somewhat differently.

This raises a set of interesting questions: if Donald Trump and I can disagree about the meaning of The Godfather, then can the movie really mean anything? And if a movie can mean anything, isn't that the same as saying that it really has no meaning at all?

Hmm…

Take romantic comedies. Sleepless in Seattle (1993) is a good one of those.

The story involves a man named Sam Baldwin (Tom Hanks) who is struggling to find meaning in the world after the death of his wife. His son calls a late-night talk show and makes Sam speak to the host, and this conversation is heard on the other side of the continent by a woman named Annie Reed (Meg Ryan) who becomes increasingly convinced that maybe she is meant to be with Sam instead of her kind but rather insipid fiancé. After a long series of mishaps and adventures, we think maybe Sam and Annie will never meet…but at the very end of the film they do, at the top of the Empire State Building on Valentine's Day, and it's love at first sight. They, and we, know they will never be apart again.

Again, what is this movie about? Sure, it's about love, and loneliness, and our deepest fantasies of finding someone to whose presence bathes us in a warm glow for the entirety of our existence.

But it is also, as are all romantic comedies, about the fact that we are beings often possessed by tremendous urges – for affection, companionship, sex, romance; for that undefinable spark that is sometimes generated between two people – and thus faced with tremendous conundrums. How do we know when we have found love? What's the right way to pursue someone you love? What's the wrong way? How should you treat someone who's in love with you if you don't love them?

These are fundamentally questions about how to act towards other people, and how to act towards yourself and the parts of that self that may not be in your control.

And that, writ broadly, is morality.

What about, say, action movies? In perhaps the quintessential one of those, Die Hard (1988), our hero, a cop named John McClane (Bruce Willis) finds himself trapped in a building that's under assault by a gang of ruthless thieves posing as terrorists, led by dastardly mastermind Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman).

So what is the primary question confronting McClane? Is it how to stop Gruber?

Actually, it's not. Prior to that, McClane has to answer a deeper question: why act at all? Why not just run away, or hide in a broom closet until the whole thing is over? Let Gruber take the money, blow up the hostages on the roof, get away clean, and then McClane can come out and make up some excuse about why he wasn't able to help.

But he doesn't do that. Instead, he risks his life to defeat the thieves. Why?

Although your answer may come to you quickly, this is probably a question you've never really thought about before.

Take a moment and pause on it. Why does John McClane stand up to the bad guys? Why do we find McClane heroic? Why do we find Gruber dastardly, or the FBI agents Johnson and Johnson both morally deficient and darkly humorous?

How, exactly, does the movie transmit these values to us? What is it in that concatenation of words and images on the screen that stirs us in this way?

This is the value of movies, and of the arts in general. They force us into a relationship with the deepest questions there are, about the meaning of our lives, the reasons we do things, and the kind of choices that should be esteemed.

Movies do this simply by telling us stories about people who may not be exactly like us (I, for one, would have no idea how to even begin cutting off a horse's head and slipping it into the bed of a sleeping man, or making a bomb out of a computer monitor and dropping it down an elevator shaft to blow up a bunch of bad guys) but are enough like us – in that they, too, are indelibly human – for us to be able to relate to them.

As I noted above, movies do this in a way that is open to interpretation and argument. This is the point of the idea that Herr Trumpf and I would likely have vastly different reactions to The Godfather. Movies are not moral instruction. They are not a "thou shalt" sermon. They cannot be, because all they do is tell stories.

Their meaning, or, better, "meaning," exists somewhere between them and us, suspended in the contested atmosphere of communal understanding. This is an atmosphere made up of our experiences, our conversations, the other movies we've seen, what we've read or listened to, and all the rest of the minutia of our lives. It is an atmosphere created by talking and listening to one another.

This atmosphere, in other words, is our culture. It is suffused with, and in part created by, movies and other works of art and entertainment – books, TV shows, music, poetry, theater, and all the rest.

And while the meaning of any single movie can be debated, in the aggregation of them – in our culture – the main lines of our national tradition are clear. We tell ourselves story after story, and the ones that have purchase, the ones that inspire imitations and variations, become our story.

This is why movies are so incredibly valuable at a time like this.

In watching a movie, we are not simply letting ourselves be swept away by what happens. We are, in fact – whether we're aware of it or not, and whether we like it or not – engaging with the ever-changing, ever-building American understanding of morality.

We are engaging with our slowly evolving cultural tradition of how we ought to treat people.

We are engaging with the complex American notion of what it means to do the right thing and the wrong thing, what it means at a fundamental level to be human.

As I suspected they might in the run-up to the election, what the MAGA faction is doing to our nation is deeply anti-American.

As people better versed in the law than I am have explained, Trump's attempt to force DOJ attorneys to break the oaths they took, his attempt to rewrite the Constitution in numerous ways, and his vesting of power in Musk without following the required protocols are all illegal under standing law, in addition to being immoral.

As people better versed in economics than I am have explained, Trump's tariff scheme is both stupid and destructive, and his decision to put Musk in charge of assigning his own company a $400M contract is both stupid and illegal.

As people better versed in international relations than I am have explained, the MAGA heel turn overseas – aligning America with neo-Nazis in Germany and the authoritarian Putin regime in Russia, blaming the Russian invasion of Ukraine on the Ukrainians themselves, planning to turn Gaza into a casino recreation resort – has forced patriotic Americans to root against their own government on the international stage.

Beyond all of this, though, Trump's actions run directly against the clear moral tradition of our culture and cinema.

From City Lights (1931) to The Grapes of Wrath (1940) to Hoosiers (1986) and beyond, the American cinema reveals a cultural tradition of cheering for the underdog. It does not, and cannot, condone putting vulnerable in chains and send them to Guantanamo and release ASMR videos on Twitter (through the official White House account!) celebrating how good it feels to be cruel. There is no place in our tradition for this kind of depravity.

Films from Night of the Hunter (1955) to One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest (1975) to The Devil's Advocate (1997) and beyond reveal a deep-seated awareness of our own cultural propensity to produce power-seeking charlatans and the importance of resisting them. They do not lend comfort to men who would seek to install themselves as dictators.

Our cinema endorses a continual search for justice, difficult as that may be, not the dismantling of the Justice Department. Go watch 12 Angry Men (1957) or And Justice for All (1979).

In more war movies than I have room to list, it promotes an evolving understanding of our role in international strife, the moments when we have erred terribly by wreaking havoc on other nations, and of the emotional destruction handed off to the soldiers we use to fight for us. It does not promote capitulation to the vilest possible anti-democratic forces abroad.

And again and again it evinces deep almost naive beliefs – perhaps the deepest in the American soul – in justice as an ideal towards which we strive and true democracy as an attainable thing.

Are American movies unimpeachable? No. Are there dark sides to this tradition, including a propensity for violence, an inclination for corporatism, a tradition of patriarchy, misogyny, and racism? Of course.

But in the main, is it impossible to think seriously about American cinema without acknowledging that it has been one of the main theaters in which the better angels of American culture have been advanced, act by act, scene by scene, frame by frame.

I'm afraid, friends, that we are in for a very bad, and potentially very long, moment.

It's time to fight, using any and every resource we have, and the rightness of our cause is no guarantee of its victory.

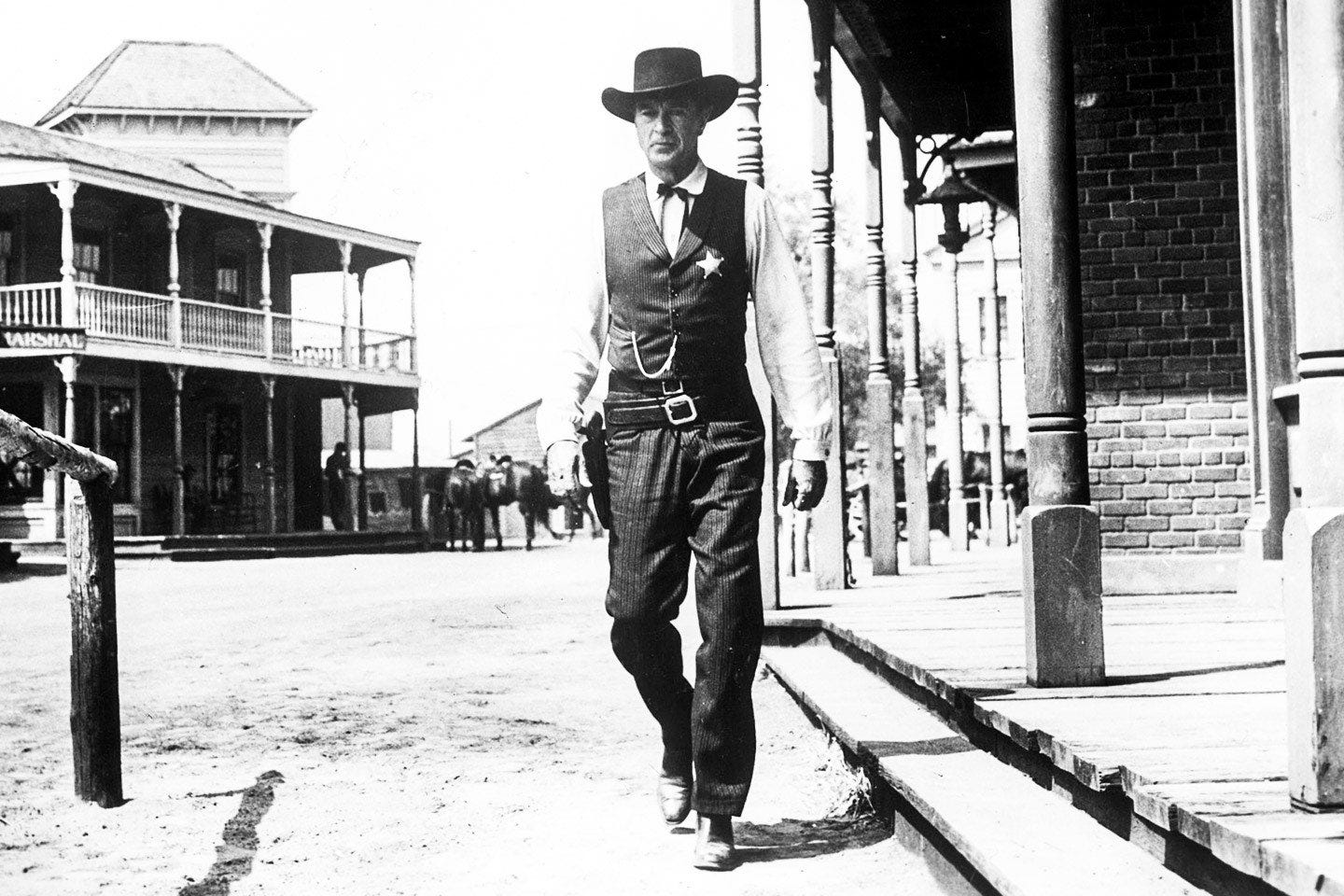

But don't lose faith. Because who do we have on our side? All of them: Rocky Balboa, Ellen Ripley, Axel Foley, Rick Blaine, Sarah Connor, Armand Goldman, John Shaft, John McClane, Annie Reed, Shane, Maria Tura, Mr. Miyagi, Major John Reisman, Detective Virgil Tibbs, Lorelei Lee, Mookie, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (both!), Martin Brody, Laurie Strode, Andrew Beckett, Wonder Woman, The Tramp, Jackie Brown, The Bride of Frankenstein, Captain Ahab and Ishmael (both!), C.C. Baxter, Marshal Will Kane, Blade, Johnny Utah, Flash Gordon, Charles Burnett's Stan, Paul Atreides, Indiana Jones, Batman, Harvey Milk, The Dude, Marty McFly, Ron Burgundy, Quentin Tarantino's Bride, Snake Plissken, Peter Venkman, Atticus Finch, Joan Crawford's Vienna, E.T., Marge Gunderson, Jim Stark, and on, and on, and on…

Great post, as always.

Your optimism is refreshing and very welcome. I both admire and envy it, I really do, but I confess that I find myself on the other side of things. I haven't gotten much pleasure from watching films lately and at times I've wondered if there is even any value to cinema at times like these beyond infantile escapism. I've been thinking a lot about Godard, who gave up every ounce of political and commercial goodwill he had generated during the New Wave in order to spend 8 years trying to develop a new kind revolutionary cinema that would be politically conceived, politically produced and would lead directly to political action, only to realize that the kind of people who would watch those films didn't need them, and the kind of people who needed them wouldn't watch them.

If I had to push back a bit on the morality of US cinema (or cinema as a whole, really) I would say that everyone thinks they're John MacLane and nobody thinks they're Hans Gruber. MAGA operates as if they are underdogs fighting against an illegitimate oppressor, despite being the establishment in every sense of the word. And the most successful contemporary films are about superheroes: millionaires operating outside the law, accountable to no one, mistrustful of (or even antagonistic to) public institutions, imposing their will on the world, to great applause. I admit I haven't been keeping up with contemporary cinema much, but I suspect I haven't missed out on too many films in the vein of "The Grapes of Wrath" or "Modern Times", you know?

I don't know., maybe I'm just catastrophizing. I hope I am, anyway...

I could read your title as What Are Good Movies In A Time Like This. I would say Casablanca, Citizen Kane, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, The Great Gatsby, My Man Godfrey, Parasite, The Social Network, The Sound of Music, They Live, Trading Places, You Can't Take It with You...