The Villainy You Teach Me I Will Execute: "Winchester '73"

In her lovely study of the films of Anthony Mann, Jeanine Basinger notes that Winchester '73 (1950) is frequently "pointed to as the beginning of the modern western." This is because of the at-times frightening, cracked depth of Jimmy Stewart's main character, in whom the frequent violence of the Western film gains an almost deranged undertone. "From Winchester '73 onward," Basinger writes, "the idea of the western hero as a man besieged by personal problems – violent and even psychotic – becomes increasingly prevalent in American films."

This seems to me essentially right (if perhaps a touch simplified, as there were many other films exploring this notion during that time), as does the move Basinger makes in tying her argument to the primary symbolic element of the movie: the Winchester '73 rifle around which everything revolves.

It’s a near-perfect gun, which we're told a number of times is "one in a thousand," meaning that it came out of the assembly process without any flaws. This magnificent weapon is passed from character to character, serving as a kind of touchstone that ties together a number of episodes that are not quite vignettes and yet at the same time not quite traditionally related elements of a plot. Basinger quotes Mann as saying that he saw the rifle as a kind of "externalization" of all of the conflicts of the film.

The idea Basinger keys on here is that through his use of technical means – the symbol of the gun, the portrayal of the troubled interiority of Stewart's main character, the connection of disparate episodes – Mann creates a film that explores the nature of (male) violence, as well as the way that violence is depicted on screen.

Rather than simply presenting violence as a kind of (usually) noble solution to external problems, as earlier Westerns had tended to do, Mann's film connected it to the psychology of the characters engaging in it. So that in the wake of Winchester '73, more and more movies began to explore the notion that the hero does what he does not because of relatively simple external strictures (the importance of stopping evil, the belief in creating a just society) but because of complicate internal conditions (traumas he's suffered, issues he struggles to deal with.)

This is a helpful way to begin to understand Mann's accomplishment, as well as the general cinematic moment through which he moved. But what interests me is what this idea suggests about not only filmmaking in the middle of the last century, but filmmaking in our own time.

Winchester '73 opens with a shooting contest being held on July 4th, 1876, to celebrate the centennial of the nation's birth, held in Dodge City and presided over by Wyatt Earp. The winner of this contest will be awarded the Winchester '73 one-in-a-thousand rifle. The action begins when two strangers ride into town: Lin McAdam (Stewart) and his sidekick Frankie Wilson (Millard Mitchell). They're hunting a man, and know that if there's a shooting contest with a prize like this one, their man will be here.

He is. Named Dutch Henry Brown (Stephen McNally), he's an outlaw and an all-around bad fellow…but also a great shot with a rifle. He and Lin end up as the finalists in the shooting competition. When Lin wins, Dutch Henry can't stand not having the prize rifle and ambushes him in his hotel room, stealing it and riding off. Once again, Lin and Frankie give chase.

This leads to the series of episodes in which the rifle moves from one person to another. Dutch Henry loses it in a game of cards to a corrupt Indian trader (John McIntire), who in turn is killed by a group of Indians he's trying to swindle. The leader of this band, Young Bull, (Rock Hudson) takes the rifle. Meanwhile, a young dance-hall girl named Lola (Shelley Winters) – who interacted with Lin briefly in Dodge City at the beginning – is riding in a wagon with her new fiancé Steve, on the way to his ranch. They're ambushed by the same band of Indians, and race into the protection of a cavalry troop camped nearby. Lin and Frankie also arrive at the same spot, and the next morning the Indians attack.

Young Bull is killed in the battle, and Lin and Frankie ride off, unaware of the rifle lying nearby. A soldier finds it and gives it to Steve, who takes it and Lola to meet up with some of his friends; these turn out to be outlaws led by a gunfighter named Waco Johnnie Dean (Dan Duryea). Waco Johnnie kills Steve to get the rifle, and then brings it and Lola to meet up with his friends, who turn out to be Dutch Henry and his henchmen. They're planning a bank robbery the next day, which Lin and Frankie arrive just in time to foil.

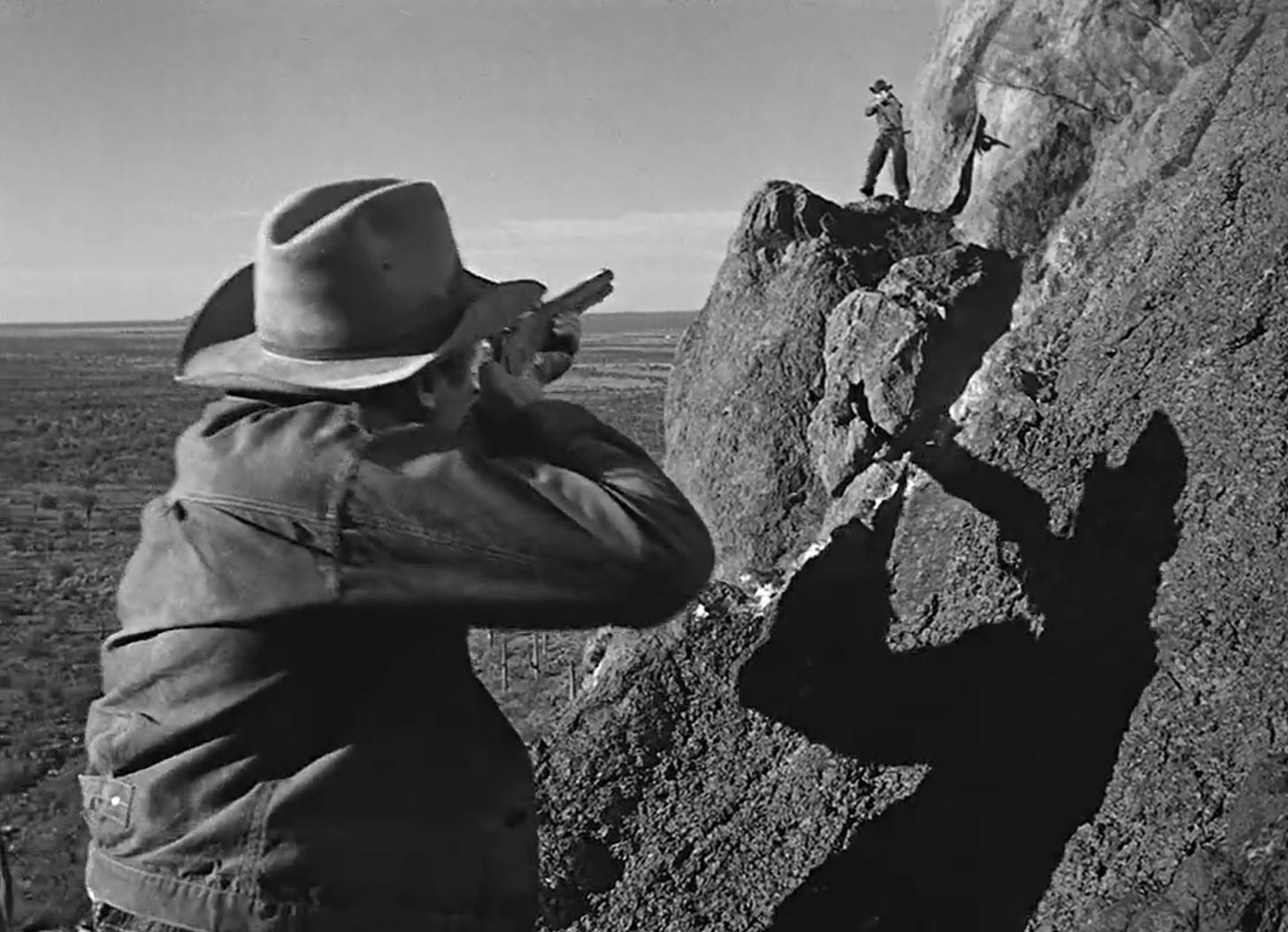

Lin chases Dutch Henry into the backcountry. Back at the scene of the failed bank robbery, Frankie tells Lola the cause of the animosity between Lin and Dutch Henry: they're brothers, and Dutch Henry killed their father by shooting him in the back. In the end, Lin and Dutch Henry engage in a shootout set among some rocky cliffs (Mann's favorite setting for a showdown like this one).

Lin kills his brother, and reclaims the Winchester '73.

As Basinger (and many others) have pointed out, throughout the film the rifle serves as a kind of totem of the psychological issues at play. It becomes the locus of the struggle between Lin and his brother Dutch Henry, and the question of who will end up with the prize stands in for the question of whose vision of life – law abiding and father-loving or law breaking and father-killing – will triumph.

It also serves as a proxy for a larger set of issues between the whites and the Indians in the West (although no film in which Rock Hudson plays an Indian can really be said to be dealing with actualities, so much as it deals with the terrors and idealizations of native peoples in the white mind), and as a mechanism for exploring the drives of the outlaws throughout, who covet it with a kind of mindlessness that is clearly paralleled by the way they covet Lola. All of this is, I think, perhaps what Mann was thinking about when he talked about the rifle as an "externalization": for each character, it becomes an external manifestation of the internal forces driving them.

But despite these layerings, at heart, Winchester '73 is a revenge movie. This is a genre (or perhaps a narrative trope) with a long and diverse history in American film. It includes things as diverse as early horror fare like The Black Cat (1934), hard-edged '60s crime films like Point Blank (1967), '70s conservative urban decay fever dreams like Death Wish (1974) and many more; it's also such a popular trope in our current moment that it seems to be the go-to for any action film that wants to consider itself steely-eyed.

Liam Neeson has built a late-career, mid-tier action film renaissance on playing tough guys out to get the baddies who've harmed his daughter or wife; movies that seem to want to be taken as higher brow, from The Revenant to Old Boy, trade in it relentlessly; and even huge enterprises like the John Wick franchise often revolve around the idea of getting back at someone for the naughty things they've done to the hero. When someone as unlikely as Bob Odenkirk starts getting in on the game – with Nobody, in which he's basically John Wick but a suburban dad – you know something's up.

One way to approach a film cycle like this one is to ask what it is in our culture that’s making people so hungry for these kinds of stories about revenge. This is an interesting question, and one that leads in valuable directions. But in relation to Winchester '73, it may be worth beginning with the observation that one thing marking our current cycle is its absolute lack of psychological complication.

When Basinger describes Stewart's character as a man "besieged by personal problems – violent and even psychotic," she's describing both a character trait and an interest on the part of the film. He's a character who’s in some sense unhinged by what he has to do, dismasted by the act he must commit. On a larger level, though, the story seems to want to raise questions about the nature of the violence inherent in the act of revenge; in particular, it asks us to question how different the main character's revenge really is from the rest of the killing that saturates the screen.

One way to understand this is to think through the presentation of the two brothers, Lin and Dutch Henry. Throughout the movie, we're presented with images that signify not so much their difference but their similarity. For example, the way they handle their rifles when they shoot – raising them slowly and at a slight angle, and then snapping them into place to fire – is identical. And when they first fire at the targets in the competition, the grouping of their shots is the same. Like the Winchester '73 rifle itself, the characters' handling of firearms carries a thematic and psychological weight: it links them, turns them into reflections of each other. They sit at different polarities, perhaps, but are still joined.

Basinger points to a scene which crystalizes this nicely. When Lin and Dutch Henry first encounter each other in a bar in Dodge City neither is armed, because Wyatt Earp has decreed that no one is allowed to carry a gun in town. On seeing each other, though, they both go for their gun, slapping the empty holster where their pistol would be. The gesture is identical, once again creating a visual parallel between the two men.

And this similarity also slips into the film's consideration of the meaning of violence: as Basinger notes, this scene is significant exactly because of the way it makes the audience aware of the rituals of on-screen killing. We've seen men draw their guns many times in movies, but now, because of the empty holsters, we're forced to ruminate for a moment on what exactly is going on here. Precisely because of its absence, the lack of an actual shoot-out draws our attention to how ritualized the moment is, and how identically shaped by it these two men are.

This comparison between Lin's hero and Dutch Henry's bad guy thus functions on many levels. They handle guns in the same way, they both want the Winchester '73, and they're both steeped in the same rituals of violence. This invites us to see Lin's quest – which is, after all, a quest to kill another human being – as something with real psychological complication. How different is he, really, from his brother? And is Lin's obsession with revenge in some sense also an obsession with violence itself?

These questions bring us back to the movie's treatment of the one-in-a-thousand rifle itself. The film opens with a shot of young boys admiring the Winchester ‘73 on display behind a plate glass window, talking about how much they'd love to have it. We then pan upwards and see grown men behind them, having the exact same conversation. From boyhood through to manhood, Mann seems to be saying, instruments of violence exert a pull.

He continues this line of speculation by continually giving us shots of men looking at the rifle with a kind of obsession in their eyes. Importantly, after the contest, the rifle is to be inscribed with the name of the winner, but this doesn’t happen because Dutch Henry steals it; this means any man who possesses will be able to put his own name on it. The rifle thus becomes a kind of ultimate treasure, the end goal of all the male characters in the film, a thing they can mark with their name so that it will carry their identity. Accordingly, again and again, they kill each other for it.

The questions raised by this are many and complicated. The answers the film suggests are equally complex but have to do, I think, with our cultural male attraction to violence. The gun is powerful. It signals potency. Its perfection offers a way for these men to perfect themselves, as if by possessing the best rifle in the world they might become the greatest man in the world. The subterranean psychosis (if that's the right word) with which Stewart imbues his character is thus suggestively tied to a male obsession with violence itself, as if having to kill one's own brother is simply an extension – different in scope, perhaps, but not in kind – of all the other killing that surrounds these characters. And surrounds us, as well, in our cinema.

Seen through this lens, the most interesting question about our own cycle of revenge movies is not about why we are so attracted to these kinds of stories, but why we're so uninterested in the psychology of violence, and the moral difficulties of revenge.

In our current films, the hero claims to be reluctant to go out and kill people. He's retired, or trying to put that life behind him…but this is simply a device used to make us like him, rather than something that brings into question his internal construction. The film always goes to great pains to reassure us that the hero is right to do what he does, that he’s a good man for doing it, and that his decision isn’t really all that complicated. He may be weary of violence, in other words, but he's not cracked, not internally riven, never, as in Winchester '73, compared to the bad guy he's pursuing or to others (like Waco Johnnie) for whom violence is actually fun.

Which is to say that in our contemporary revenge cycle (with some notable exceptions, of course) there simply is no psychology of violence, either on a character level and a symbolic level. Instead, the equation is brutally simple and never questioned: someone injured the hero, and so he has to get revenge. There are no discordant notes. Everything is satisfying.

The full implications of all this are of course beyond the scope of a Friday afternoon rumination. But it does seem to me to suggest the edge of something terrible, or at least terribly sad: a moment in which the audience sees itself as irretrievably harmed, and wants nothing more than to see the violence of revenge as both entirely justified and entirely uncomplicated.

Enjoy this piece? Subscribe for free to receive a new essay on film in your inbox every Friday. And if you have a moment, please share this piece with anyone you know who’s interested in movies!