Several days ago, there was a brief internet brouhaha when someone claimed that Clint Eastwood was the best right-wing director in American history.

Click through to the above link to the original tweet if you'd like, but there's really no reason. For the cardinal rule of Twitter, as with most social media sites, is that the purpose of any post is as much to get clicks as it is to convey information; which is to say that you should never assume that anyone there fully believes what they're saying. More importantly, you should never assume that they have any actual knowledge of the things they're talking about.

But the main reason the original claim – and virtually the entire "discussion" that followed – is silly isn't really due to the qualities of the people participating. Instead, the silliness of the opinions arises from the absolute lack of anything concrete in them.

From one point of view, this lack of actualities is a terrific advantage: if your ultimate goal is to get clicks (and perhaps to reinforce your self-image by watching yourself throw out "big ideas" and having numerous people respond) then tying any grandiose claim into anything like a specific fact is a nearly impossible to overcome hardship.

In other words, to take examples from the thread I linked to above, if you claim Eastwood is "right-wing" without ever doing more analysis than mentioning his weird empty chair speech at the Republican National Convention, or searching for pseudo-academic language about how he (and Jean-Pierre Melville) make films about an "individualism of violent honor amidst total depravity" (and I must pause here to ask this inane individual to go watch Army of Shadows before offering any further opinions on Melville), or lumping David Lynch and Tarkovsky and John Hughes and John Ford into a group of directors that if you're someone who wants to trumpet your "liberal" values on the internet you should consign to the dumpster fire of "wrong ideas" (Ford's films are "'good' films from the perspective of craft, etc even if the politics are abhorrent" sniffs one commenter);– if you're going to do all of this macho broad-brush posturing, then it's actually not just convenient but necessary that you never give us a reading of a film, or talk about the specifics of its plot, or its place in film history, or anything of the sort.

Because if you did dive into the details, then you'd be forced to make an argument, instead of spewing warmed-over platitudes. And making arguments about art is hard.

The question about any film (or director) is not whether you can get out your "conservative" or "liberal" stamp and dip it in your red ink and forever brand the work so that no one ever has to watch it again. The real questions relate to things like how a film is political – in the specifics of it, from plot to character to camera work – and the way it fits into history and culture, and, deepest of all, what it means for a film to be political. Does it show something loaded with political content? And how do we interpret that showing? Does it seek to convince the viewer of a specific worldview of political position? And if so, how exactly does that convincing operate? And perhaps most importantly in terms of the relationship between film and culture, what does it tell us about the politics of the society that produced it?

These are extraordinarily complex questions, and the process of coming to terms with them doesn't really have much to do with blathering on Twitter. Instead, it involves a long aggregation of real discussion, the back and forth of actual arguments about specific details of the work, out of which consensus arises…only to be challenged by a new idea or new generation, beginning the conversation all over again. In some sense, that is, questions about art are never really answered, because the point of art isn't to pin it down like some butterfly in your intellectual insect collection, but to try to engage with it, love it, let it move you, ruminate on how it affects you, and then talk about that with other people.

All of which is not to say that there are not movies (or directors) with politics, because there very clearly are; it's just that, as they say, the devils of those politics are in the details.

So let's look at some details and see what we find.

The basic story of Michael Winner's Death Wish, from 1974, goes like this. Charles Bronson plays a middle-aged New York City architect named Paul Kersey. The opening of the film makes it clear that he's a liberal guy: he describes himself as a "bleeding heart," and when a fellow architect makes a derogatory comment about the kind of people who are involved in the wave of muggings and murders inundating the city, Kersey argues that it's important to remember that these crimes arise in part out of social conditions. We later find out that Kersey abhors violence and was a conscientious objector during the Korean War.

But these beliefs change quickly when his wife and daughter are assaulted during a home invasion by three young Freaks, as they're labeled in the credits (one is played by a baby-faced Jeff Goldblum). Kersey's wife dies of injuries sustained during the attack, and his daughter is so traumatized that she retreats into a vegetative state from which she never recovers.

In response, Kersey becomes violent and vengeful. This first manifests when he loads two rolls of quarters into a sock and walks the street, waiting to be approached by a mugger, whom he smashes with his new weapon. But the real turning point comes when his firm sends him to Arizona to work on the plans for a housing development. There, he witnesses an "Old West" reenactment in which a sheriff shoots and kills some bad guys; Kersey is also given a gun as a souvenir by the Arizona land developer he's assisting (this man also offers up some choice pontificating about the beauty of a wide-open land where a man can experience real, old-school American freedom, as opposed to the horrors of city life).

Kersey then returns to New York and picks up where he left off, but this time with the gun instead of his quarter-filled sock. He prowls the streets and when he's approached by muggers, he kills them. Soon, the city is aflame with the legend of its vigilante killer. An allergy-afflicted cop named Frank Ochoa (wonderfully played by Vincent Gardenia) is assigned the case and slowly tracks Kersey down (with the help of a beat cop played by a young Christopher Guest wearing a lot of rouge). But just as Ochoa is ready to make his arrest, he's pulled in by his superiors and told that the legend of the vigilante is good for their political careers – the crime rate is down, and the people of the city feel empowered – and so Kersey is not to be arrested, but simply told to leave the city.

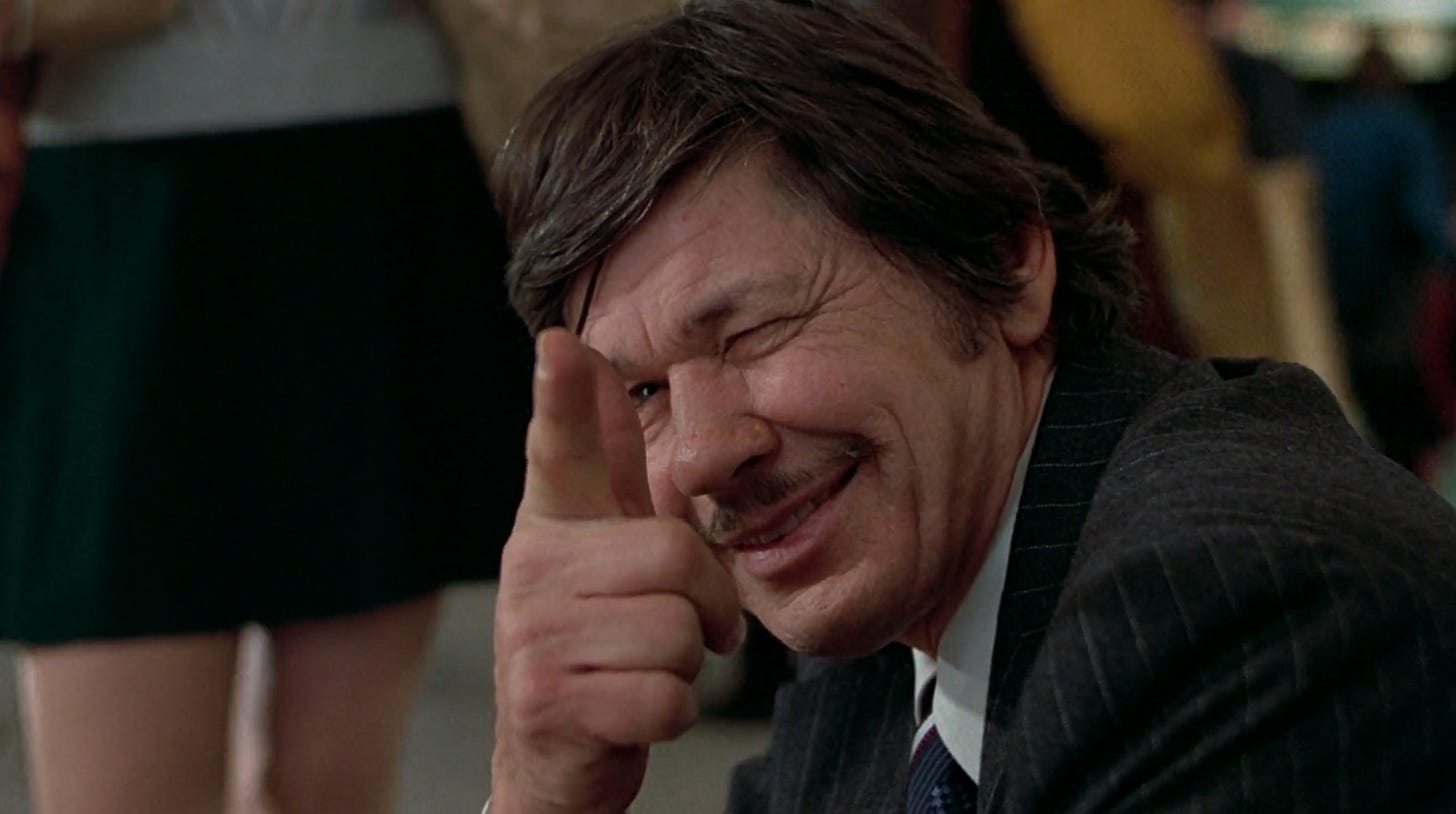

And in the end, this is what happens. Ochoa confronts Kersey with the evidence that he's the vigilante, and tells him to get out of New York or he'll be arrested. Kersey gives a half smile. "Before sundown?" he asks, still riffing on the dream of the Old West he picked up in Arizona. The final sequence of the film takes place in Chicago, the city to which Kersey has relocated. He sees some hoodlums harassing a young woman, gives them a scary smile, and points his fingers at them in the shape of a gun…

Death Wish has long been labeled as being "conservative" in its world view. There are many good and understandable reasons for this – it paints urban life as terrifying, offers up a vision of the Old West as the repository for real American values, valorizes gun ownership, promotes the notion that a "good guy with a gun" is the solution to the things that plague us, etc. – and I'm certainly not here to argue that it's actually some kind of misunderstood socialist parable.

But I do think it's worth thinking about the actualities of this conservatism, and what they tell us about American culture, and history, and film. So, with my usual caveat that any real discussion of the movie would take far more time than I have to give to it on this Thursday afternoon in Wyoming, here are a few provisional notes.

Let's start off with some various and sundries. First, take the director, Michael Winner, who was, oddly enough, English. This certainly complicates the notion of Death Wish as an example of American conservatism, does it not? At the very least, it raises the question of the degree to which this is an outsider's view of the country, rather than an American view. It doesn't invalidate readings of the film as an "American" one, I don't think, but it does remind us that the connection between a director and political readings of their career are often not reducible to Twitter-length summaries.

In this same way, one should note that Winner's first collaboration with Bronson is the almost too fascinating for words action flick The Mechanic, from 1972. In that film, Winner took a script about a gay assassin and his gay protégé (I am not being metaphorical, and neither was the original script – their relationship was explicit) and removed only the most naked references to their homosexuality, leaving the rest of the story intact, as well as inserting all kinds of visual clues to their now (mostly) subtextual relationship. A strange, complicated, and glorious film it is; conservative catnip it is not.

Should this affect our reading of Death Wish? Perhaps. Perhaps not. But it should cause us to put the brakes on the notion that Winner is in his filmmaking persona some kind of unrepentant fascist, in perhaps the same way that actually watching Unforgiven or Letters From Iwo Jima, or Mystic River might complicate our understanding of Clint Eastwood, or watching Fort Apache or The Grapes of Wrath or Young Mr. Lincoln might complicate our understanding of John Ford, and so on.

Another layer of all this (and now we're getting to the actualities of the film itself) begins to unfold itself when we think about the film's relationship to American history. Through a number of not-so-subtle elements – the trip to Arizona, several characters' ruminations on the nature of civilization, and Kersey's own actions and dialogue – Death Wish explicitly connects itself to the Western movie genre. This is obvious; what's fascinating is the way it does so.

As I've noted several times elsewhere, one of the basic elements of the Western genre is the conflict between civilization and the wilderness. In some Westerns, the equation runs such that the civilizing influence of the westward tide of colonization is a good thing, and the wilderness (often represented by Native Americans and/or outlaws) is an element to be conquered; in others, the values are reversed and the wilderness is a source of strength and purity, while the colonizing advance of civilization is a threat to those things. And sometimes films mix these two ideas, or strand their characters between them.

What Death Wish makes clear, for anyone who isn't already aware of it, is how deeply certain American conservative beliefs are also tied into this narrative. The notion of the Old West as a place of violent near-anarchy that could only be "tamed" by a good guy with a gun (bringing civilization to the wilderness), as well as the notion of the Old West as the last place of true freedom where a man could be a real man and defend his manliness against the lily-livered un-manly (defending the spirit of the wilderness against the encroachment of civilization) both lie at the root of what we often think of as conservative America's relationship with guns, as well as its conception of social interaction itself. In Death Wish, both elements of this mythos are in play. New York City is the stand-in for the moral corruption of "civilized" urban life that needs to be tamed with the gun; at the same time, Kersey is the stand-in for the Western gunslinger who's a repository for the nobility and freedom of that wilderness.

Just in case we're too dense to pick up on all this, the film makes sure to put it into dialogue as well. In the very first scene, for example, Kersey and his wife are on vacation in Hawaii, and Kersey suggests that they make love on a secluded beach. "We're too civilized [for that]," his wife responds. "I remember when we weren't," is his reply. And in the theater, the liberal film critic's head explodes. Don't you see! Weak old city-fied civilization his here tied to a lack of freedom and a lack of virility! It constrains Charles Bronson from making manly love to his wife, goddamnit! And then later in the film, he loses the constraints of that sorry-ass liberal civilization by acquiring a gun and wiping out some bad guys, thus restoring his true manhood!

No wonder the film is seen as having some conservative bona fides.

But…(for there's almost always a "but" in this things)…what the film also reveals is the strange incoherence at the heart of this view. Because where does Kersey get the inspiration for his redemptive quest? From an Old West reenactment put on for tourists. And who created the myth of the American West in the first place? In large part it was Hollywood, that bane of conservatives everywhere.

To take the most famous example, there was virtually no such thing as a "quick draw" in the historical American west. The idea of two gunmen standing in the street and matching reflexes by drawing their pistols in an attempt to assassinate one another is a fiction popularized by Hollywood for the purposes of on-screen tension, visuals, and themes (and then subsequently taken up by the pulp novelists of the 20th Century). Which is to say that it's a purely Hollywood trope that's being referenced in the closing of Death Wish, when Kersey tells a hoodlum to "Draw!" (Tellingly, the hoodlum has no idea what the hell he's talking about.) And the film has the intelligence, or the grace, or simply the luck, to make this clear through the Old West reenactment in Arizona: Kersey is getting his ideas from a fable put on for the purposes of entertainment.

What's being winkingly (or perhaps unintentionally) referenced here is the that the Western gunfight is perhaps best understood as a storytelling convention latched onto by a segment of society in need of founding parables about itself. Another way of putting this is that it's a retroactive attempt to apply a kind of individualistic, honor-code understanding to a locale (the western part of the continent of North America) that was, like so many others, the scene of a fair amount of chaotic violence. This is not dissimilar to the view, and self-view, of the pre-20th Century American South as a place obsessed with "honor," which is, in no small part, simply a society-scale psychological attempt at compensation through revision: "Slavery can't be horrible, because we're honorable!" (As an aside, if you'd like a better understanding of the South, go read Faulkner, the greatest self-chronicler it ever produced (and perhaps the greatest of all the American novelists), and the ins and outs of the real workings of all this will become much more clear.)

All of which is to say that one of the things we learn about the American conservative relationship with the gun from Death Wish is that it's founded in large part on a myth fabricated by the entertainment industry. In exactly the same way that Paul Kersey takes a cheesy stage show to be a road map for a livable reality, the famous steely-eyed realism and protection of traditional values propagated by gun-lovers operates in large part from the projection of their own yearnings – through the medium of "heroic" fictions – back onto the past, precisely so that those yearnings can be used to provide some kind of historical "justification" for their actions. (And this is not to pick on American conservatism in particular; contemporary American liberalism is rife with its own set of disastrous and ridiculous contradictions.)

This kind of fracturing, of incoherency, runs beneath the surface of nearly the entirety of Death Wish. If you want another example, what about this pesky question: why is Death Wish structured so much like a horror film?

There are clear indications throughout that Kersey is in some way going mad (American Psycho-style) as he descends into his murderous quest. When he first builds his sock full of quarters, he tests it out in his living room, in a scene in which Bronson does a magnificent job of embodying a kind of frantic, repressed energy, swinging the weapon violently around his head and smashing up one of his own chairs. Later, after he's begun using his pistol to do the job, his son-in-law (the husband of the Kersey's catatonic daughter) visits his apartment to find that he has painted the walls a garish shade of orange and is listening to music so loud that they can barely converse. Again, Bronson plays it so that the character's protestations of normalcy clearly cover something going wrong inside him. And during that scene, Kersey serves his son-in-law liver, while in the scene immediately following, we find out that Kersey's next victim has been shot in the liver. The strange connection of eating an organ and then killing someone by destroying that same organ is ghoulish, yes; at some other level (and something intentional is going on here, obviously) there's the suggestion that Kersey is turning into some sort of deranged predator, rather than a noble "good guy with a gun."

This turn towards horror is further emphasized by the way tension works in the closing act of the film. There, the detective Ochoa edges toward becoming the protagonist. Why do I say this? Because what's pulling us forward, what's making us want to keep watching, is exactly the question of whether he's going to be able to stop Kersey. In other words, Kersey is now the malign force in the movie, the disruptor of society, murdering (as do so many killers in horror films) people who have indeed sinned, but needing to be dealt with if order is to be restored. This reaches its apex in the final shot of the film, when Kersey makes the finger pistol gesture into camera and we cut to black. This moment functions in exactly the same way as the famous shot at the end of Halloween in which Michael Myers' body is missing, or the ending of Friday the 13th, in which Jason leaps up out of the lake to grab Alice, or of Carrie, in which Carrie's hand flies up from the grave. Kersey's look at the hoodlums functions to give us a jolt, a frisson, a suggestion that the violence and danger isn't over. And in doing so, it aligns him with the monster from a horror film.

But why use this convention, if Death Wish is a conservative reverie about a good man cleaning up a corrupt liberal city? Why suggest that he's somehow like Michael Myers or Jason Voorhees? Is the implication that conservative viewers will be thrilled by this idea? That they will be titillated by vigilante violence? But doesn't this seem to suggest a rather critical view of those viewers? There are many ways to approach this, many arguments that could be made. I'll suggest only one: there is at the heart of American culture a buried sense of unease, if not revulsion, about its own violent tendencies.

As the Southerners wished to insist that they were honorable, as there was a need to demand that the colonizing violence in the West could be sanitized in the symbol of a white-hatted man giving a black-hatted man a fair chance before he blasted him into oblivion, there is a need to compensate for the love of the good guy with the gun doing god's work in murdering the scum. It's perhaps too much to suggest that Ochoa is the real protagonist of the film throughout, but there is somewhere at the heart of the movie's conservatism an incoherent yearning for the very thing it disdains: a man of society, doing his job, trying his best to keep us all together without resorting to the murderous violence the film fetishizes.

Again, socialist parable this is not. But it's certainly a more complicated piece of art than can be disdainfully summarized and then discarded as propaganda, at least for those of us who are actually interested in real discussion. And for those of us who are interested in American culture as a whole, it serves as a good reminder that it's worth watching these kinds of movies if we want to come to grips with our surroundings.

And…oh yeah, I forgot, I did have one more thing: why the hell is it called Death Wish anyway?

Enjoy this piece? If you want to support me, please share tylersage.substack.com with anyone you know who's interested in film, culture, or ideas. Also, as this is an entirely reader-funded enterprise, I'd be eternally grateful if you would consider subscribing for $5 a month. For this meager amount, you'll receive every piece in full, get full access to the archives of this site, and greatly contribute to my ability to keep writing.

If you'd like to read more of my work, my book on William Klein's cult classic superhero film "Mr. Freedom" is now available in the Constellations series (Auteur/Liverpool University Press). Read an excerpt from the introduction here. If you'd like to buy a copy, you can do so here https://global.oup.com/academic/product/mr-freedom-9781800856943?lang=en&cc=us.

Thought provoking and brilliant as always!