I should perhaps open by reminding you of the "mostly" in the title of this journal.

Journal, you ask? Indeed. While Substack, the corporate body that owns this site, terms it a "newsletter," this seems to me to be a rather silly descriptor for what's going on here, as I clearly give you no news at all in my weekly missives. And, although I sometimes refer to them as "essays," the things I write in this space are largely off the cuff, a kind of thinking out loud. I have neither the time nor the inclination to do the kind of revision and re-thinking that would constitute the creation of an actual essay; if you're interested in reading my approach to that sort of thing, I have a book coming out this summer from Liverpool University Press, which I'm sure I will promote heavily and shamelessly on this site once we get closer to publication.

In any event, in my head, and now hopefully in yours, this space serves as nothing more (or, significantly, less) than a journal, in which I develop and then follow my thoughts, mostly on the subject of film.

Ah, there's that word again. Mostly. Which means not always. And this week I've been thinking about Bob Dylan's lyrics.

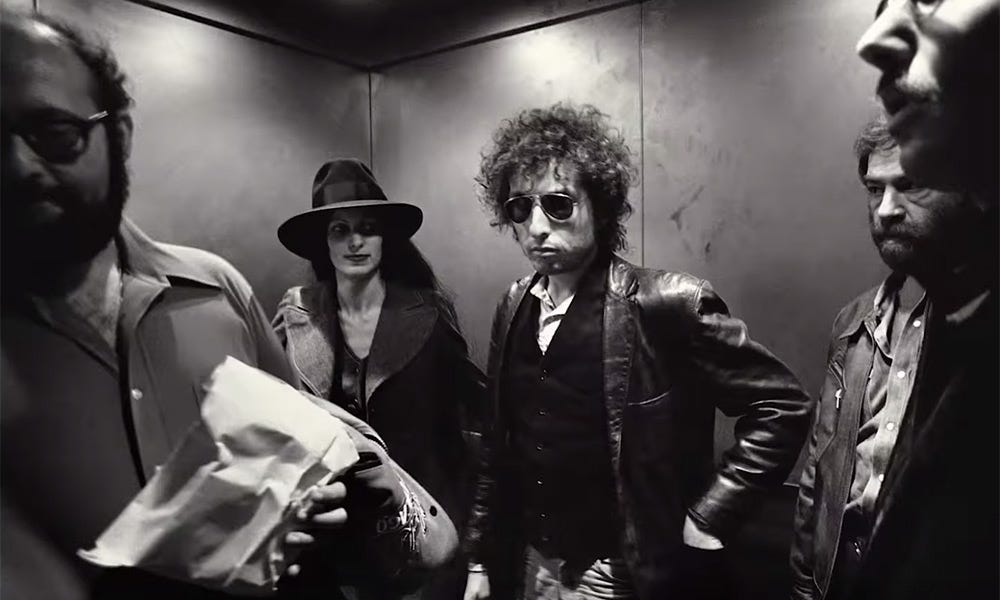

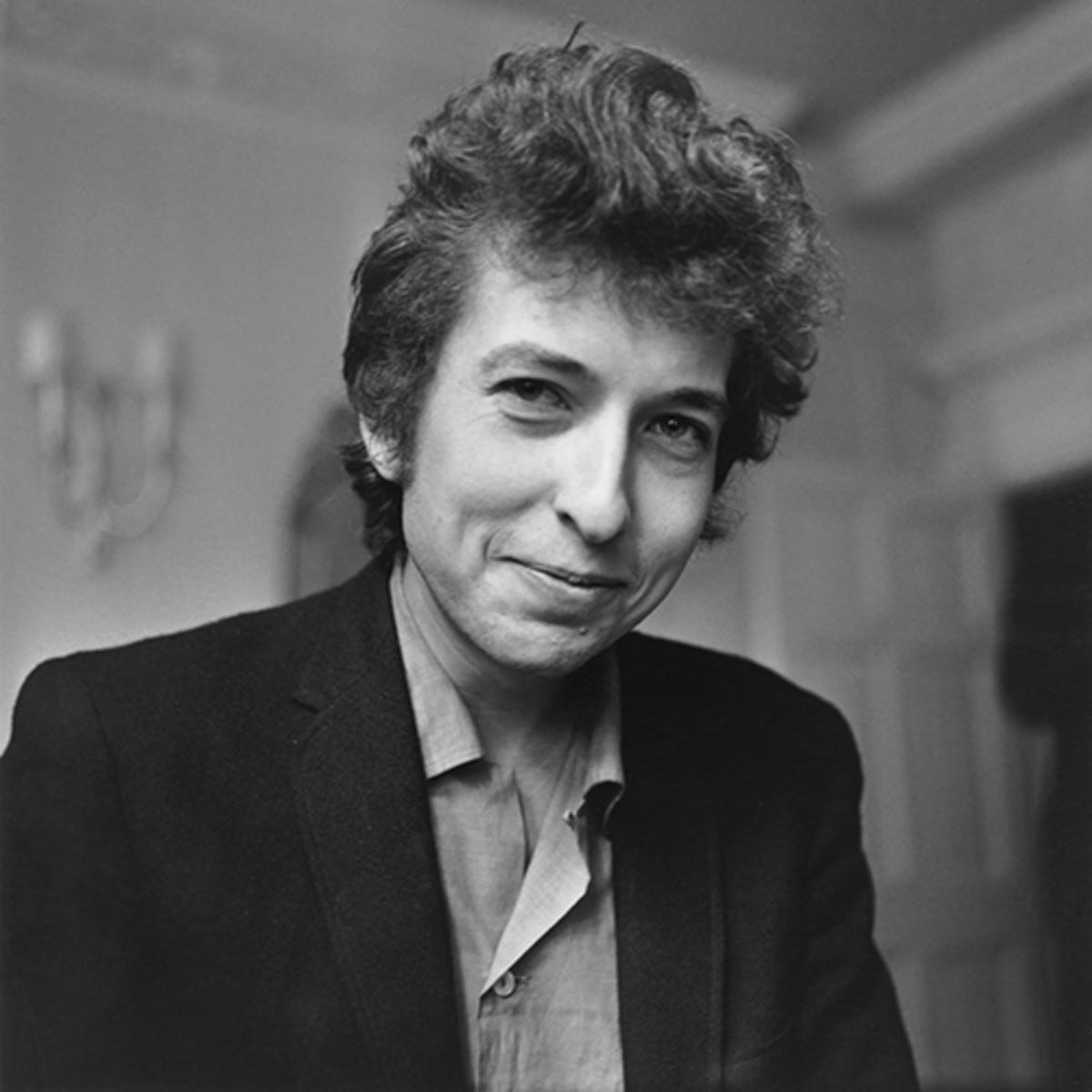

Dylan is a controversial figure in his own way, and it is precisely one of the elements of that way that I've been thinking about this week. His most ardent admirers seem to see him as an almost divine figure, inspirational, and possessing some kind of higher insight. I once taught on the same faculty as a man who claimed – truly, by all accounts – to have written the first ever doctoral dissertation on Dylan's work; he was famous for shoehorning the songwriter into every course he was assigned to teach in the English department, because, for this professor, the pantheon of American letters began (and perhaps even ended) with the man once known as Robert Allen Zimmerman, from Hibbing, Minnesota.

Dylan's detractors see him as boring, or annoying, or having a bad voice, or not as good as Joni Mitchell or their other favorite songwriter, or any of the other things that detractors say about famous artists. They say he's a faker, or overrated. They cackled with glee at the accusations of hypocrisy when Dylan – that famed protest artist from the '60s – appeared in a Victoria's Secret ad in 2004, and have continued to cackle as he has continued to license his songs for commercial use in the years after that.

Fights like these don't really interest me, outside of the joy of hollering at my friends when we're drinking beer and listening to music. What does interest me is the way Dylan is controversial, the kind of now you see me, now you don't, and now I'm leaping out of the brambles to poke you in the eye with a sharp stick element to him that has so infuriated (and inspired) people over the years.

It's the kind of personality trait that would lead him to say, to an interviewer in Playboy magazine in 1966, when asked what led him to start playing rock and roll and in the process alienate many of his folk music-loving followers:

Carelessness. I lost my one true love. I started drinking. The first thing I know, I'm in a card game. Then I'm in a crap game. I wake up in a pool hall. Then this big Mexican lady drags me off the table, takes me to Philadelphia. She leaves me alone in her house, and it burns down. I wind up in Phoenix. I get a job as a Chinaman. I start working in a dime store, and move in with a 13-year-old girl. Then this big Mexican lady from Philadelphia comes in and burns the house down. I go down to Dallas. I get a job as a "before" in a Charles Atlas "before and after" ad. I move in with a delivery boy who can cook fantastic chili and hot dogs. Then this 13-year-old girl from Phoenix comes and burns the house down. The delivery boy – he ain't so mild: He gives her the knife, and the next thing I know I'm in Omaha. It's so cold there, by this time I'm robbing my own bicycles and frying my own fish. I stumble onto some luck and get a job as a carburetor out at the hot-rod races every Thursday night. I move in with a high school teacher who also does a little plumbing on the side, who ain't much to look at, but who's built a special kind of refrigerator that can turn newspaper into lettuce. Everything's going good until that delivery boy shows up and tries to knife me. Needless to say, he burned the house down, and I hit the road. The first guy that picked me up asked me if I wanted to be a star. What could I say?

This was an impromptu moment, just a guy having fun, riffing. But it was also in response to an action on his part – shifting away from playing folk music and going electric – that inspired such vitriol in his own fan base that his erstwhile supports were yelling "Judas" at him from the cheap seats. His response to that (which you can hear at approximately the 7:54 moment of "Ballad of a Thin Man" on the 1966 "Royal Albert Hall" recording)? He turned to his eclectic backing band – composed on that night mostly of the members of the band that would come to be called The Band, because they backed him (Levon Helm had left the tour at that point, which you can definitely hear if you listen to the drumming, and now we're wandering into the territory of trivia) – he turned to his band, after a fan called him Judas, and said: "Play it fucking loud."

So he's a contrarian. Or at least that's where we might start in describing him. But how does this connect to his songwriting? Because this contrary nature – or at least certain elements of it – this hiding in plain sight, this armature of words, is exactly what makes him a great lyricist.

On first glance, "Desolation Row," may seem to be the same kind of nonsense riffing as the quote he gave to Playboy. Fairly quickly, though, the sensible structure of the song comes through. (I’ve pasted a link to the song below, and he complete lyrics can be found here.)

It opens with nine verses in Dylan's gothic fabulist register, describing a town with a street or neighborhood in it called Desolation Row. The first verse is representative of the whole:

They’re selling postcards of the hanging

They’re painting the passports brown

The beauty parlor is filled with sailors

The circus is in town

Here comes the blind commissioner

They’ve got him in a trance

One hand is tied to the tight-rope walker

The other is in his pants

And the riot squad they’re restless

They need somewhere to go

As Lady and I look out tonight

From Desolation Row

The scene is set. A hanging has recently occurred, which has been made into postcards. There are sailors in town, and a circus; there is the blind commissioner tied to a tight-rope walker and a restless riot squad looking for action. And looking over all of this is Dylan – or the "speaker" of the poem, in the parlance of academic interpretation – who is with a woman.

One could pause here to really parse the language, delving into the combination of the grotesque (the hanging) and the carnivalesque (the circus), the image of impotent authority (the blind commissioner) combined with a kind of sad sexuality (the hand in the pants), the intimations of violence on the horizon (the restless riot squad), etc.

One could also push into the realm of more extended criticism: it would be fascinating, for example, to work through the intimations of the connections between this tight-rope walker and the one who appears in the opening of Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra, in the scene in which the revelations brought to the people by Nietzsche's protagonist (speaking on behalf of the philosopher) first begin to be revealed. Or one could make the comparison to Steinbeck's Cannery Row, from his 1945 novel of the same name, with its collection of misfits and its sadness and euphoria.

One could do all of this, that is, if one had the time to write a full essay. Instead, though, let's cut to the chase. This is a song about heartbreak over a failed relationship.

Where does that become clear? Well, I noted that there are nine verses of description of this town with its Desolation Row. These include many descriptions, quips, and characters, from Cinderella and Ophelia to Cain and Able, from the hunchback of Notre Dame to Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, from Shakespeare's Ophelia to someone known as Dr. Filth. It's all very opaque, if suggestive and beautiful; and on its own, it all seems impossible to make sense of.

And then we get to the tenth verse, which goes like this:

Yes, I received your letter yesterday

(About the time the doorknob broke)

When you asked how I was doing

Was that some kind of joke?

All these people that you mention

Yes, I know them, they’re quite lame

I had to rearrange their faces

And give them all another name

Right now I can’t read too good

Don’t send me no more letters no

Not unless you mail them

From Desolation Row

The singer has received a letter, from a person who hasn't appeared yet in the song, and who isn't living on Desolation Row. And the agreement that opens the phrasing – "Yes, I received your letter yesterday" – makes it seem as though this person has been on the singer's mind since the beginning, and perhaps has even been the person that the song has been directed to. The letter is about something inconsequential, a broken doorknob, and it includes a moment in which its author has asked the singer how he's doing. His response – "When you asked how I was doing / Was that some kind of joke?" – starts to bring things into focus, for we know how he's doing. Terribly. He's on Desolation Row, surrounded by all this tragedy and borderline madness.

And what is the letter writer (let's call her a she) doing? She's worried about her broken doorknob and talking about people that they both used to know; for his part, the singer has had to rearrange these people in his memory, trying to forget them or give them new identities. Finally, he notes that he "can't read too good." This is not because he's illiterate – he's just referenced Shakespeare, Victor Hugo, and a pair of modernist poets, among others – but perhaps because he's crying. And he would rather not have any more letters from this writer, unless she too is living on Desolation Row.

In sum, this verse seems to indicate that the singer is heartbroken, because his relationship with the woman has ended. Desolation Row is a kind of metaphor for the emotional neighborhood one finds oneself in at these moments; its denizens are sad, playful, complicated, chaotic attempts to describe the feelings he has been experiencing, as if the only way to really try to capture the experience of a foundered relationship is to build a dreamlike world that reflects the real emotional one.

Thus, this last verse wonderfully rearranges in retrospect our understanding of what has come before: all of what we might have taken for nonsense is instead an attempt to put emotion and human experience – that monstrously complicated thing that Jorge Luis Borges once compared to a book containing an infinite number of pages – into language.

This attempt is, I think, perhaps the one that lies the most deeply at the center of a great deal of artistic endeavors. We are all stuck in this world, trying like hell to understand ourselves and each other. And what we are trying to understand – ourselves, our experiences, our emotions, the world itself – occurs to us chaotically. Sights, sounds, feelings, thoughts, events, things we only become aware of after the fact, things we cannot possibly articulate because they are inchoate, that "data of the senses" that philosophers are always talking about. And along come the artists to say, "Hey there, let me try to help by putting some of this into a song, or a story, or a painting, or whatever other medium I feel drawn to trying to articulate it in."

So Dylan's method here is to try to put the feeling of heartbreak into extended metaphor, set to music. (Although I'm not really talking about it here, one cannot take the music out of a song and think about only the lyrics any more than one can take two wheels off of a car and still expect to drive to Denver.) But, as I said at the opening, what I've been thinking about isn't so much the "meaning" of the song (always a tricky concept, and one I've probably been overly-reductive with), but the particular way that Dylan tends to write.

There is, in "Desolation Row" and throughout his work, a kind of covering or disguising of his emotion; an almost petulant refusal to admit that he's feeling what he's feeling, or, better, an attempt to pretend that he's not feeling it at all; a playing-it-off as nothing ("Don’t think twice, it's alright," he sings in another song that's about how much it's actually not alright); and this attempt to deny what (he knows) cannot be denied seems to me precisely one of the things gives so much of his work so much of his power.

Put differently, why is it that someone trying to articulate emotional devastation (or fury, or outrage, or love, or any of the other things that make up a deeply-lived life) would do so with nine verses of vivid description that seem to be about something else entirely? Why search so hard for metaphors for emotion that are so opaque as to border on nonsense, while never quite falling into nonsense? Why be so playful, why refuse to be pinned down, why refuse to admit that you're feeling what you're feeling, except obliquely in the final verse, when that admission seems to slip out, almost against your own will?

The answer seems to me to be that pretending that things are not what they are is actually a way of engaging with feelings that are too intense to be openly faced, and at the same time protecting oneself from that very intensity. And it's the very need for this protection that signifies the immense force of the things at play.

Dylan's career-long near-comedic treatment of emotional conflict ("An’ I told you, as you clawed out my eyes / That I never really meant to do you any harm"), the wry understatement ("Only one thing I did wrong / Stayed in Mississippi a day too long") and the downplaying of raw emotion (I can make it all match up, I can hold my own / I can deal with the situation right down to the bone / I can survive, I can endure / And I don’t even think about her…Most of the time);– in all of this, the denial serves as a testament to the power of what's being denied.

For how better to explore the overwhelming nature of emotion itself (and perhaps life itself) than to make clear the degree to which he, and we, struggle to keep it in check?

When the fan called Dylan "Judas" for betraying folk music and playing rock and roll, the response was to play rock and roll as loudly as possible in that fan's face. When the reporter asked him about it, the response was to cover the truth – I did it because that's what I wanted to do, goddammit! – with a comedic rambling answer that in its refusal to admit that he was furious about people trying to tell him what to do with his music testified to exactly that.

And in "Desolation Row," the heartbroken singer covers that heartbreak by describing it for nine long verses as anything but heartbreak, before breaking down at the end and admitting that he only wants to hear from her again if she will admit that she's as heartbroken as he is.

Of such self-compelled and reluctant admissions are some of the best insights into being alive made.

Enjoy this piece? If you’d like to read more of my work, my dystopic noir novel “The Committers” is now available in paperback and e-book format here. Read the first chapter for free here.

You can subscribe to “Thoughts Mostly About Film” for free to receive a new short rumination (mostly) on film in your inbox every week. And if you'd like to support my work, don’t forget to share this piece with anyone who might be interested!

I read something that made the last verse even more interesting than your interpretation, specifically about the doorknob. The key is the word "about". Mentally change it to "around". He received the letter around the time the doorknob broke. The doorknob that would have let him open the door to Desolation Row and leave...hence leaving him trapped there. Its like a final snap and realization that you will never leave desolation. A lot heavier than an innocuous line about the letter writer's doorknob to anywhere breaking.

This was a really interesting and thoughtful piece. I’ve thought about this song for over fifty years, and you gave me some important insights. Thanks much.