Here's a game I like to play sometimes: what would an alien think if they flew down to hover over our lovely nation and watched one of our movies?

This thought came to me again recently after a viewing of that glorious old Christmastime chestnut It's a Wonderful Life (1946). After a few moments of reflection, the answer that seemed best was that our bemused alien would probably think something along the lines of, “Man, those are some sorry, deluded sons of bitches.”

You may not remember this if you haven’t seen it in a while, but It's a Wonderful Life really is an astonishingly good film, full of mature insight, packed with a startling range of emotional registers, and capable of generating a rare attachment between protagonist and audience.

And yet contemporary American culture is not mature in any sense. It exists within a frighteningly narrow emotional register. And it seems virtually incapable of empathic attachment. But here we are, returning to this movie year after year and deluding ourselves into thinking it has anything to do with us.

So why do we do this?

Well, if you're one of those people who likes to feel optimistic about our beloved country, my advice is that you probably shouldn't think about questions like this.

But as long as you're here…

Despite its astounding irrelevance to our lives, the plot of the film is as deeply ingrained in our sense of holiday culture as any there is.

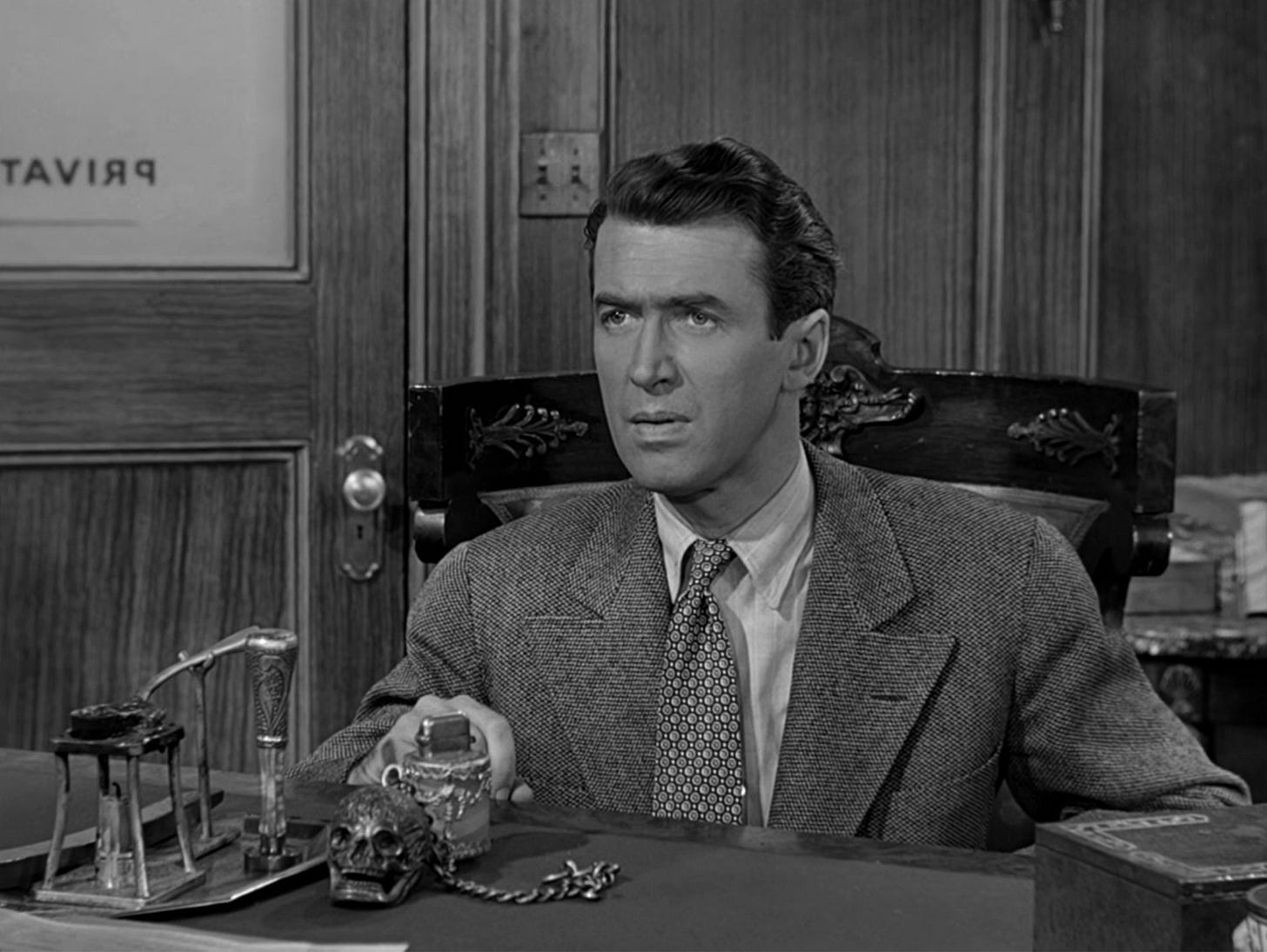

An angel named Clarence (Henry Travers) is assigned to assist a struggling human named George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart) on Christmas Eve. The proximate cause of Bailey’s anxiety is the fact that the Building and Loan he runs is about to go under because his uncle lost a good deal of money; the longer-term cause is that he has achieved none of the dreams of his youth, which included travel and adventure and the doing of big things.

He has been a good person for the entirety of his life, but that's not enough to counter his overwhelming despair. He is on the brink of suicide.

Clarence helps Bailey by showing him what the world would have been like had he not lived: his town is a place of far less happiness and far more misery, run by the film’s villain, an evil old financier named Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore). Bailey realizes that he does want to live after all, and at the end of the film the townspeople – all of whom he has helped in one way or another over the course of his life – gather together to raise the money to save his Building and Loan.

The film ends with all of them gathered together, full of Christmas cheer, singing “Auld Lang Syne.”

It's emboldening, heartwarming, and a nice reminder of what the good life might look like in some idealized universe. In these ways and more, the film propounds a set of values that really are quite important.

And the film's divergence from our own sense of the world begins with the fact that we don't share those values in any recognizable way.

Begin with the film's views about the purpose of life.

In It’s a Wonderful Life, the gross amassing of wealth is presented as an irredeemable evil. Mr. Potter, from his physical presence (given particular verve by Barrymore’s performance) to his moral beliefs, to his thematic resonance, is incorrigibly bad.

His goal is simply to make as much money as possible, and this, in the eyes of the movie, is an indefensible choice. Set opposite him are George Bailey and the regular people in the town, who value human connection, friendship, and dignity.

Can any rational observer argue that this represents the ideals of contemporary America, even in its most idealized form?

The pursuit of wealth as the highest form of accomplishment is so deeply ingrained in us that the college-aged youth have repurposed the world “sellout” into a compliment. We adulate moral dimwits like Elon Musk. We equate financial success with knowledge and wisdom. We watch endless shows about monied people with more botox than humanity.

One of the highest ambitions of the next generation is to be an influencer, dancing around on camera and convincing other kids to buy junk. The dream of social media itself – this vast, fake, technicolor world that has laid itself over ours like a terrifying Halloween mask – has nothing to do community uplift or moral betterment or anything remotely related to the ideas at the center of It's a Wonderful Life; it is instead about individual recognition, celebrity, and easy profit.

For vast swaths of our citizenry, to be is to receive the fatuous adulation of strangers pushing a button on their phones like hypnotized automatons, and to succeed is to be able to buy the same plasticized contraptions that everyone else has, go to the same beaches, eat the same expensive food, and post it all on Instagram.

It may be true, dear reader, that you, or your friends have not been lassoed into the mad pursuit of wealth (or earnestly believe you have not been), but one cannot say the same thing about American culture as a whole and keep a straight face.

But the strange nightmare of modern America runs far deeper than our TikTok algorithms.

You will note, if you are a contemporary viewer of It's a Wonderful Life, the relatively muted role (to our sensibilities) that the concept of "family" plays in it. The central social unit in George Bailey's life is not actually his family. It is the town of Bedford Falls itself: his relationships with the variety of people around him are the ones that give his life meaning.

This is a nearly inconceivable concept today.

The Family! The Family! We're inundated with the idea that The Family is the most important thing it is.

We can't turn in a circle without seeing an ad for some piece of Hollywood tripe proclaiming that the reason we do everything we do is The Family, or bumping into someone squinting wise and misty-eyed into the distance and declaring that the very point of existence itself is The Family, or having our ears blown out by someone hawking one way or another to achieve “Generational Wealth” (dear god, what a benighted term) to ensure that no one in The Family ever has to do anything so mundane as actual work ever again.

But aren't all these people and advertisements right? Isn't The Family the only reason to live, and hasn't it always been?

No. Wrong. Bad reader. Haven't you ever seen a movie or read a book from sometime before the 21st Century? The radical centrality of The Family to all things American is a new invention.

If you doubt me, ask yourself these simple questions.

Where was the sentimental centrality of The Family in the works of John Ford, or Alfred Hitchcock, or Billy Wilder or Francis Freakin’ Ford Coppola?

In how many everloving movies do Humphrey Bogart or Cary Grant even have kids?

Why do such broad swaths of pre-code films, as well as “Women's Pictures” from the '40s, suggest, more than subtly, mind you, that the family is not the boon of every woman's spiritual life but rather the greatest threat to it?

Where was The Family in the work of William Faulkner or Willa Cather or Emily Dickinson or Walt Whitman or Herman Mellville?

Was the original title of Copland's Appalachian Spring actually My Family Enjoyed the Appalachian Spring and Everyone Else Can Go Fuck Themselves?

No, it wasn't.

There was once, in the great history of this country, an idea – and this is made explicit in It's a Wonderful Life – that things like civic life, participation in the community, and the building of an existence that extended beyond the walls of our own homes were actually essential to our spiritual survival.

The reason that George Bailey's life has been worthwhile, to make the point clear, is not because he has provided for The Family and can die knowing that his kids and their kids will be millionaires too regardless of how many people had to work in Chinese sweatshops to make it happen.

No, according to the film, his life has value precisely because he has extended his reach beyond that narrow realm. He helped the people of his town, and they helped him.

The film's vision of goodness is a communal one.

And that, my friends, is another thing that no rational person can argue exists with either force or relevance in our nation today.

Finally, there is the film's conception of human character.

What a fascinating word, “character,” originally emerging as it does from the ancient Greek “kharaktēr,” meaning “to engrave,” or “something imprinted on the soul.” How indefinable and yet how grand. If we have character, we are honorable and decent all the way down. It’s written on our souls.

And how important this idea is to the movie's presentation of George Bailey!

He is a man of character above all else. He saves his brother's life, he singlehandedly prevents his town from succumbing to financial panic during the Great Depression, he helps poor immigrants buy their own homes, he sacrifices his own dreams, he loves his wife so dearly that seeing her sad and lonely in the George Bailey-less vision of the world shown to him by Clarence is the final thing that makes him truly understand his own importance.

And if you think you can make an argument that these things matter in American culture today, you are, to put it plainly, a stone fool.

I hate to bring this up, because it's like sailing into San Francisco Bay and saying, "Hey, did you see the big bridge?" but a majority of this country has just elected a rapist and felon to be not only the single most powerful person in the world, but also the man who will be the public representative of the entire nation.

It does not take a genius to see in this the fact ours is a moment when things like avarice, lying, and cruelty are not disdained but lionized. For Trump has those things imprinted on his soul, the way other people have true character imprinted on theirs.

The folks who live off of making excuses for one another will claim that Trump doesn’t really reflect the moral state of the nation or the people who voted for him. They will splutter and squawk about how the election was really about inflation or trans panic or all the rest of the fig leaves they love to scatter about.

But I'm sorry, I really do feel like we should be honest.

It's my genuine belief that an excuse like “Oh, I’m definitely against raping people, but I just don’t care about it as much as I care about my eggs costing $4.29 instead of $3.87,” doesn't constitute evidence of a strong personal ethics.

And I just cannot help but think that folks with real character don’t manage to convince themselves that, “Well, I don't really like the idea of putting ten million people in concentration camps while we try to figure out how to send them back to their shithole countries, but if it stops some boy in Punxsutawney County from playing on a girls' sports team, then I guess I’m all for it.”

If you want to argue that saving a few bucks at the store or preventing someone from switching genders is more important than teaching our kids that cruelty, criminality, power-hunger, and rape – because if nothing else, let's just be honest about what's at stake – are things that ought to be punished instead of rewarded, well that's up to you.

But what you cannot argue with any seriousness is that our culture shares the belief in the importance of character that illuminates It's a Wonderful Life.

And so, to return to our alien floating along in geosynchronous orbit over Iowa City, watching the flicking glow of our televisions this holiday season, why the hell do we keep watching this movie that has so little to do with our lives and our culture and the choices we make?

Perhaps the alien is right, and we are a bunch of deluded sons of bitches who actually think that it still represents us.

Perhaps, like so much else in our culture, this film and others like it are simply lies we tell ourselves, conveniences that allow us to continue living the way we're told to live, just so much white noise we use to drown out our souls' complaints.

Or perhaps not.

Perhaps there is in the attraction these movies have for us something sadder, more human, more beautiful.

Perhaps a film like It’s a Wonderful Life serves as a sort of lost dream of some different way of living that we can still fleetingly glimpse. An atavistic memory still surviving in shreds and pieces out there in the ether, just at the edge of our grasp. A faint reminder of something that used to seem good and noble.

And perhaps, if we immerse ourselves fully enough in it, we can almost begin to believe in it again…

In the same way that many Americans manage to ignore that all their favorite movies are about defying fascism (Star Wars, Lotr, Harry Potter...), many forget that Trump, Elon, Bezos... are Mr. Potter.

In so many ways, this is my favorite film. "Casablanca" is also in the running. The two have more in common that I thought.

Also, "Just remember this, Mr. Potter, that this rabble you're talking about...they do most of the working and paying and living and dying in this community. Well, is it too much to have them work and pay and live and die in a couple of decent rooms and a bath?"

You are so dead on the mark! Our national willingness to endorse an evil, sick man as world leader, in the name of ridding our country of "invading" peoples and for the promise of more cash in our wallets, etc., etc.,---that willingness and blindness will certainly lead to myriad destructive problems. Could the Christian Right zealots make all aspects of government and society theirs to control? Study the Bill of Rights; what distortions and impingements are happening before our eyes? Human greed and fear overtake any political system eventually; are we living through that societal maturation point right now? Do we have recourse and can we hope? And how do we live our lives?