I Have Absolutely No Sympathy For You If You're On The Internet

In Which I Try And Mostly Fail To Maintain Some Human Compassion

Hi. Welcome to "Thoughts Mostly About Film," a space in which I write occasional pieces about movies and American culture. If you find these thoughts entertaining, feel free to subscribe to receive them in your email inbox when they appear, or to share them with your friends using the buttons below.

I'm basically a live-and-let-live guy. In normal times, it takes a fair amount to really get my dander up. But these are not normal times.

Recently I've been confronted with a line of thought that I find to be so absurd that it threatens to decimate what little faith I have in the ability of our contemporary discourse to come to grips with the places in which we find ourselves.

This disgust was crystalized for me on a recent walk with my insane dog around the streets of Los Angeles. On this jaunt, I listened to a podcast on which Chris Hayes interviewed Jia Tolentino, whose recent New Yorker piece "My Brain Finally Broke" is about how she feels as though she's losing her ability to comprehend the world.

Or, as she puts it in the opening of the piece:

I feel a troubling kind of opacity in my brain lately—as if reality were becoming illegible, as if language were a vessel with holes in the bottom and meaning was leaking all over the floor. I sometimes look up words after I write them: does “illegible” still mean too messy to read? The day after Donald Trump’s second Inauguration, my verbal cognition kept glitching: I got an e-mail from the children’s-clothing company Hanna Andersson and read the name as “Hamas”; on the street, I thought “hot yoga” was “hot dogs”; on the subway, a theatre poster advertising “Jan. Ticketing” said “Jia Tolentino” to me. Even the words that I might use to more precisely describe the sensation of “losing it” elude me. There are sometimes only images: foggy white drizzle, melted rainbows in a gasoline puddle, pink foam insulation bursting between slats of splintered wood.

Now, my sense is that not many of you are much interested in the specifics of writing criticism (Why, in that first sentence, do we shift from a visual metaphor (opacity) to a verbal one (illegibility) to a physical one (water draining out of holes) that mean quite different and almost opposing things (not able for light to penetrate vs. not being able to comprehend vs. being full of holes)? Does she mean that she literally looks up the meanings of words like "illegible" after she writes them to see if their meaning has changed, or is this just flowery metaphorical language? Because if so, how long did it take her to get this dang essay written? etc.)

These rather pedantic observations aside, it is true that one gets the sense from this piece of writing of what it is really, as far as we can tell, going on with Tolentino (and, she seems to be presuming, whether rightly or wrongly, the rest of us).

The pace and number of events seem to be threatening to overwhelm her, and as a result of this, or perhaps a cause of it (?), she increasingly finds herself trapped in a world of image that seems to exacerbate her sense that the world itself may not even be understandable anymore.

In the podcast, Hayes seems blown away by the perspicacity of these sorts of observations. He notes that he has recently seen any number of images on his phone – he mentions an AI-generated bit on TikTok that tries to convince folks that homeless people are pitching tents on busses in Chicago – and has been astounded by his growing inability to tell real from fake.

In other words, Hayes too seems to feel as though his brain is being "broken."

(One more note on language, before I leave those lofty environs. In this case, "broke" is contemporary slang that functionally means, like so much on the internet "like, really, really bad and weird and, like, totally just so important." Here I'm thinking of one of the famous phrases that brought this into modern usage, which is that a picture of Kim Kardashian's butt (or some other such fantastical imagery) "broke the internet." Obviously, the internet was not broken in any real way by said image; what happened, instead, was that a lot of people looked at it and commented about it, so that for a moment that image of a butt seemed really, really, incredibly, transcendentally important, so much so that people had to come up with language for that feeling; in the same way, it's safe to assume, I think, that Tolentino's brain is not really "broken" in any serious way – my assumption (which I certainly hope is not too presumptuous) is that she's working on another piece at this very moment, maybe even lining up more podcast spots to promote her article, as well as shopping and eating and doing laundry and tossing about pithy cultural observations at cocktail parties and all of the rest that one could not do if one's brain were really "broken.")

Now, it's important to note that Tolentino's piece, and the genre it's a part of, are well intended. They seem primarily to be an attempt to give voice to the feeling that many people have of being overwhelmed by all the bad and terrifying happening in the world.

This is fine and important, although her approach is perhaps a bit more emotive (like a baby yowling about having to sit in its own poopy diaper) and a little less explanatory (helping folks understand what's actually happening) than might strictly be helpful. In my opinion. But I do understand that there's a noble intention behind pieces like this. Many of us are feeling overwhelmed right now.

And it's also important to note that these two individuals are presumably quite smart. Hayes (a host on MSNBC, who recently wrote a book on the exact topic of our relationship with our phones) seems like a well-informed guy, and Tolentino is writing in The New Yorker for god's sake, getting paid astounding sums of money (by my lights) because of her ability to put words on the page.

Despite this, however, I find the idea they're propounding to be only a touch short of full-on bat-shit crazy.

In fact, as this discussion has evolved, it has left me with a reaction I think is probably the opposite of the one it intended to create: I have absolutely no sympathy for the plight, or more accurately "plight," of folks like these.

Perhaps we should begin by noting something so obvious that it seems to have gone unnoticed by far too many folks: reality is not actually under assault in any way, shape, or form.

If you are someone who doubts this, take a moment to step away from your computer, or put down your phone (if you still possess the ability to do so) and go outside. Touch a tree or a brick, or talk to a human being. You will be astounded to learn, no doubt, that these things – the outside, trees and bricks, actual living human beings – still exist.

Now, these elements of reality are certainly under threat in some ways. And perhaps even because of you and me.

The tree you just touched, for example, exists under the threat of climate change, which is exacerbated by the demands of producing the extraordinary amounts of electricity needed every time one of us assholes decides that it's just absolutely vital to use AI to determine the marital status of a celebrity or the best way to cook a tuber; on top of that, the living human being you just spoke to may now exist under the threat of madcap physical violence because of the regimes and politicians we have all sleepwalked into existence.

So those definitely constitute threats.

But is the nature of reality itself under threat? Are the things external to our consciousness actually bubbling away into some kind of imagistic soup because of the impossible force of our own agony? This, friends, is just silly.

But it does present us with an interesting problem.

If smart people are terrified by the feeling that somehow reality itself is disintegrating, but reality itself isn't disintegrating, then what's actually happening?

To return to the language of the title (with which Tolentino may or may not have had anything to do, incidentally), this in turn raises the question of what it is that has finally "broken."

Is it inside of our brains or outside of them? And what are the possible reasons for it and responses to it?

As these are questions with which it seems we are all going to have to deal with for the foreseeable future, and as it would be in terribly bad taste to criticize someone else's thinking and writing without offering up my own to the same sacrificial alter, here are a couple of ideas.

As I noted above, reality, in an ontological sense (the fabric of existence itself) is under no threat. There will always be things external to us, comprehensible or not. Such is the nature of being human.

What has happened instead – as Hayes gestures at in his anecdote about being befuddled by the "images" of homeless people camping on Chicago busses – is that an extraordinary number of people have developed what I think can accurately be described as a monumentally bizarre relationship with the little screens that surround us during so much of our waking lives.

Put differently, what is under assault is not reality, but people's relationship with reality, as mediated by their phones. This is not, of course, an original idea, but one that has been obvious for many years now. Tolentino attempts to grapple with it by describing her phone as

a device that makes me feel like I am strapped flat to the board of an unreal present: the past has vanished, the future is inconceivable, and my eyes are clamped open to view the endlessly resupplied now. More than a decade of complaining about this situation has done nothing to change my compulsion to induce dissociation anew each day.

I find this, I must say, very strange.

To explain why, I'll take her thoughts in reverse order. At the end, Tolentino notes that she is, in fact, aware of the deleterious effect that living her life through a seven-inch screen has on her. She also notes that she has been complaining about this for ten years without said complaining (strident as it may have been) ever leading to an ability to "change [her] compulsion" to "induce dissociation" every day.

To which I might respond with questions like:

Do you really think complaining is an effective way of treating this compulsion?

Can you honestly not conceive of a future?

Are you literally unable to, as I suggested above, just put your phone down and step outside? For if you could do that, I really do earnestly suspect you would discover that reality is in actuality still fully intact around you.

Now, to these simple (if admittedly snarky) questions, I imagine that some folks will respond as follows: "Bro, you don't understand. The point is that we can't get off our phones. It's an addiction."

To which I would say, fair enough.

I recently had a conversation with a friend in which he voiced the notion that his kids are furious at him because he, and the other members of our generation, helped them get hooked on their phones when they were too young to know better, and now they (the kids) have to deal with the repercussions of that lifestyle/addiction/whatever language you want to find for it. Which sucks.

Point well taken.

But that's not quite what's happening to the adults, is it.

Say we take the notion of a physical addiction to the phone very seriously, to the point of asserting that through the repeated endorphin hits our phones give us, the brains of heavy users have in fact been re-organized such that their need to look at their phone is a physiological compulsion, or something like that – again, language is important here, and I'm (obviously) not a neuroscientist, but I take it you get my drift.

The point is that if we take the addiction metaphor seriously, then I think we are forced to ask the following question: How would we respond to a meth addict writing an article about how their sense of reality is being destroyed?

We would (I hope) be sympathetic. But I think we all understand that sympathy would not be the sum total of our judgement if Tolentino's article had instead been titled "My Brain Finally Broke Because Of All The Meth I've Been Doing."

Nor would pure sympathy be our reaction to a sentence like "More than a decade of complaining about [my meth use] has done nothing to change my compulsion to induce dissociation anew each day."

To put just a little bit of a finer point on it, among our many responses to that article might be, "Yeah, no shit. It's a destructive addiction, as you yourself just insisted."

Or, to bring it back to the podcast, I think it's a totally and completely fair to offer the following riposte: "Chris Hayes and Jia Tolentino, you are goddamn adults! Are you honest to god complaining about your habit of being on TikTok watching videos of homeless people pitching tents on busses, and expecting us to give a flying fuck? And on top of that, are you really expecting us to share your stunned incredulity that this habit has messed up your brains? And, incidentally, how long has it been (if ever) since you've been on a public bus, if that idea seemed plausible to you for any length of time at all?"

To put it differently, please don't tell me that the claim at stake here is that our addiction to our phones has warped our sense of reality. Because to announce that as if it's some kind of astounding is new discovery and then pass this off as cogent journalism or commentary actually makes me sad. Bitter and furious, yes. But also sad.

You didn't see this coming? It never occurred to you that spending hours and hours every day watching the kind of idiotic shit we all watch on the internet, and engaging in the social media that we all know makes the sewers that sewer rats live in look like the Four Seasons – it never occurred to you that this would mess with you heads?

Honestly, it's like someone coming up to you at a party all weepy with a plug of bloody toilet paper in their nose and trying to tell you about how they just can't get a handle on their life, making you want to scream in their face: "Do you think maybe this has to do with all the goddamn coke you've been snorting?!"

I have no sympathy. None.

In fact, the more I've thought about this, the more bitter and furious (but also sad!) I've grown. This is because I've started to suspect that there is in fact a deeper tragedy at play here.

The problem with our phones is that they threaten to reduce us to rats pushing buttons over and over again to induce a stimulus response, yes. Button. ENDORPHIN! Button. ENDORPHIN! Button. ENDORPHIN!

But, there is an equally insidious problem.

This is that the internet has created entire generations of people who have become convinced of their own omnipotence. We now seem to believe that we are actually seeing, and actually can and should have an opinion – that we expect everyone else to take seriously, by the way – on every single thing happening in the world.

Or, as Tolentino puts it, many of us honestly really do think that our "eyes are clamped open to view the endlessly resupplied now." The language here is not just grandiose and apocalyptic. It also hints at an all-knowingness.

But this "endlessly resupplied now" does not, in in fact, include enormous amounts of the actual "now."

For example, if one had the temerity to ask her, "That's really fascinating, but does your phone show you the patch of high-county forest in Colorado that I'm thinking of right now?" she would have to say, of course, No.

Her phone cannot give her access to the experience of being in that patch of forest, or, hell, of being in your back yard at dusk when the fireflies are coming out, or on the roof of your building at dawn when the air is fresh and perfect.

What our phones give us is actually a relatively narrow slice of existence. They show us a certain kind of human clamor and claim that it's all there is. They remove contemplation and actual companionship and many, many more things from our experience; they threaten to turn the quiet places of the world so invisible that we forget that they exist.

You can see, I think, what I'm after. In a crucial way, the screens around us represent a terrible narrowing of our understanding of life itself. They block out whole swaths of it, and reduce other whole swaths of it to a ceaseless electronic murmur.

But because they are insidious little devices, the impression they give us is exactly the opposite.

Our phones make us feel – falsely, I hope it doesn't need to be said, although I think it probably does – that we have an on-the-ground, insider knowledge of the life of anyone else in the world who has a social media account. But they don't give us this. We don't see those people, ever, in an un-curated moment, one they have not shaped and crafted and chosen out of dozens of takes.

Beyond that, our phones make us feel as if a quick search of a topic or subject is enough to speak with absolute authority about it. (To take an example that crops up in my life all the time, you would be astounded by the number of well educated, smart people I meet who feel the need to imply that they have seen a movie or read a book when, it is obvious to me, who has actually seen some of these movies and read some of these books, they have in fact only skimmed a summary online.)

This promise of expansive never-ending knowledge is intoxicating. It's empowering. It gives us the feeling that we're in touch with the whole world at once and that on any and every given topic we have the right and duty to point our phones at our own faces and scream out our deepest convictions.

It is a promise that you don't ever have to not know something, that there is no topic you cannot master. If you need proof, consider that this is exactly the promise that is being hyperextended by AI, which is, of course, the newest tendril these devices are extending into our minds. If you doubt this, watch any commercial for AI, all of which, if stripped of the specifics of their target audiences and ad-crafted verbiage, run as follow: "Does it matter if you don't know [how to do X job/how to write Y report/the way to impress Z person/the basic rules of etiquette]? No! Because now you can use AI to pretend like you know everything, and do any job for you, and thus become successful and rich!"

What power! What exhilaration! And it is, I think, the belief in this that lies at the root of this mysterious sensation that reality itself is breaking.

I am a known fan of cynicism, so take that under advisement, but it's my deep suspicion that the order of operations goes thusly:

People's phones have convinced them that they are functionally omnipotent beings who can know and opine about everything of importance in the world because every important thing in the world is there in their social media feeds.

This gives them a remarkable feeling of control. They feel as though they are no longer at the mercy of the rules of reality, which insist that we are small, limited beings confronted with a world that is larger, more multitudinous, and less comprehensible than we are comfortable with. (See: Our need for religion, science, philosophy, art, etc.)

But then they are confronted with a truly terrifying idea: what if their phone isn't something that allows them to see the entirety of "reality" at once? What if, instead, it might be more rightly described as a device which has an extraordinary, singular power: it's amazingly effective at manipulating them? This idea freaks them out.

Suddenly, the source of their incredible feeling of power, agency, and being heard – the internet as accessed through their phones – has been turned against them. All those good feelings are flipped upside down. If the phone is something through which they can be manipulated, then instead of feeling power and agency they feel impotency, lack of agency, and an inability to do anything.

Because this experience is overwhelming, people decide that what has happened is in fact that their brain has become broken, or, even worse, that it's impossible to even understand what reality is anymore.

What we are seeing is not any significant change in reality, in other words.

What we are seeing is the expression of a very human feeling: I really believed in my ability to have a mastery over the world, and I associated that with goodness and forward progress and connection to every single person, and now I'm desperately watching the truth come out. I feel like a sacred promise – My phone makes me powerful! – has been revealed as a lie.

And you know who has no goddamn sympathy at all?

Even as I write this, I find myself thinking that it is perhaps something for which I should have sympathy. These people are going through something hard.

But why then do I instead find myself feeling like scaling a cliff and urinating down on them from such a great height that they feel it as a rather misty, odorous rain?

To understand this, it might help to turn back to the addiction metaphor.

Part of the attribution of addiction to something is the understand that in some vital way, the people suffering from it are not at fault, or not beset by some kind of character flaw. (This is one of the basic moves that goes along with accepting that addiction is a disease).

Say we grant this. Say we grant that all of you out there lugging your phone addictions through life are simply at the mercy of a disease, and are struggling to do your very best to rid yourselves of it.

This still leaves the question of what your addiction is doing to the rest of us.

Someone in the grips of an addiction to drugs can destroy themselves physically, and destroy the people who care for them emotionally and financially. But you all, you phone people, are doing a lot more than that.

In the middle of an environmental crisis, your insatiable need to use AI to make yourselves seem smarter and more competent than you really are is creating a demand for electricity so great that it threatens to put a final stake through our ability to control the emission of carbon. So you are not simply "breaking" your own brain. You're destroying the world in ways that will have terrible effects on people for literally hundreds of years.

And on top of this, you phone people are perpetuating the exact system you are wringing your hands about. Did it never occur to you that your habit of getting your chuckles by scrolling through endless short form videos of teenagers trying for 16 hours to hit a cheese puff with a hot dog so that it flies through an onion ring balanced on their friend's nose is the only driver of social media, in the same way that our habit of eating cheap meat is the only driver of the factory farming system?

Now, although it may seem like I'm being judgey, what I'm really not judging is the act itself. What I am judging is your pretense of befuddlement and helplessness, and your resounding claim that we should feel sorry for you.

To return to what I feel might be a slightly better alternative title for Tolentino's piece, why don't we just call it: "My Brain Finally Broke Because I Did So Much Meth And Then Got Your Kids Addicted To It And Burned Down Your House, But The Main Point Is That You Should Feel, Like, So Much Pity For Me."

But I just don't.

Finally, we are at the rub. Because all of these people who are complaining about how reality is broken are, in fact, making plenty of money and chatting away on podcasts and raising kids and doing all the rest of it, and one of the main things they are complaining about is that they feel like they're under assault from other people's suffering.

A large part of the second half of Tolentino's article devolves into a listing of the terrible things happening in the world, a recitation of all the news and images assailing her from her phone.

Yes, this is difficult. And yes, as I said above, I understand the point of trying to give voice to what people are feeling.

But I also think it must be said that what these folks seemed to have perhaps missed is that the horror of what people are capable of doing to each other is not somehow a break from reality.

The terrible things humans do is a constituent element of reality itself.

Many of the phone people out there are educated enough to know that terrible things have always happened in the world. In fact, I would venture that many of these folks are more educated than I am, so I know that they know about (to list things off the top of my head), the insanity of the American occupation of Iraq, the continuing blithe acceptance in our society of both homelessness and gun violence, the Vietnam War with its bombings and Agent Orange and My Lai and all the rest, the assassination of Patrice Lumumba and the destabilization of an entire society, the Soviet Gulags, Belgian atrocities in the Congo, the Holocaust, the torture prisons of various regimes in the Middle East, the genocide of the Herero, Yeats writing about what the Second Coming will constitute, the eradication of much of the native populations of the Americas, the Crusades, the Black Death, and on and on, back through history.

But somehow, despite their knowledge of this, the phone people have the temerity insist that it is only now that reality is breaking.

Does this not suggest someone who is not engaging with reality itself, but is instead almost impossibly sheltered from it? Someone who, when confronted with the actuality of all the things that have been happening to people (but just not to them) all over the world throughout much of history, insists that this actuality feels so terrible that the truth must be that reality itself is breaking?

Again, it's not contempt for this feeling that I'm trying to express, but contempt for the fact that confronted with it, what it occurs to them to try to articulate is that the most important thing is how everyone else's suffering makes them feel.

Every time they do this, they add to the problem.

Intentionally or not, they are insisting that the real reality – the one that is breaking them – is the one they view through their phone. Not the reality of history, not the actual things that are happening in the world, not a sober view of the truths of human existence. On top of this, they are insisting that the most we can do about it is yowl like a newborn with that terrible sensation flooding its crotch.

And while we're on the topic of babies, doesn't this entire discourse stink to high heaven of naivete?

We have always manipulated each other through image. We have done it from the first cave painting of a semi-realistic, semi-metaphorical animal (for what is a metaphor but a lie that attempts to open a truth?) to modern movies…if by "manipulate" here we mean to present reality not as it concretely is, but in such a way that it induces a reaction or shares an idea or makes a point.

But there are constructive manipulations, and destructive manipulations.

The destructive ones are those you see on your phone. They are destructive in large part because they are fed to you by algorithms that – again, I hope this doesn't need to be said, but I think it probably does – do not have your best interests in mind.

The feeling that the world is breaking is an state induced by the destructive manipulation of image and sound. It is not intended to show you reality. It is intended to keep you on your phone. And, even more insidiously, it has the effect of convincing you that reality is your phone, rather than the heads that are being busted by the batons, or the smoke from the tracts of the Amazon being burned down to give you hamburgers.

What you are feeling is not the sensation of reality breaking. It is the sensation of being controlled. Of giving away some significant portion of your humanity, and then bemoaning that choice.

Ans I feel such an extraordinary, almost inhuman disdain for this that it makes me wonder about my own sense of empathy, my own sense of decency. Perhaps those things have been broken by all of this too.

I do, however, have something positive to offer. Which may be surprising, given the tenor and topics of this piece (when my wife read the bit above about the "misty, odorous rain," she looked at me impishly – impish is one of her finest modes – and said "Jeez. Remind me not to get on your bad side.")

But, and I mean this seriously, why would I write something if I didn't feel I had something to offer? Why would I write something, the sole purpose of which was to make me feel better by screaming into the void?

I spoke above about constructive manipulations.

Those of you who have been reading me for long enough probably know exactly where I'm going with this, but one of the most vital constructive manipulations is art.

When you create a piece of art, what you are not doing is simply pointing at some extant piece of reality and saying: Look! (That is what you do when you are on a walk and see something beautiful or interesting, which I will remind you again is something that's possible if you put down your phone.)

No, when you create a piece of art, you are arranging pieces of the world – whether that be words or images or objects or anything else – in order to help, or force, or urge, someone else to experience something. In other words, you are manipulating both reality itself and another human being.

If you make a horror film, for example, you are prodding someone into feelings of tension and terror; if you write a love poem you are opening them up to experiencing a sensation the way you have experienced it.

This is manipulation, clearly. You are trying to move the world, trying to move another human being. But it is constructive: it works to expand the actualities of human experience.

And you will notice, if you pay attention closely, that because of this there is a stark contrast between the way art makes you feel, and the way the slop on your phones makes you feel.

So, if you are someone who has felt lately that reality itself is coming unglued, I have a very simple experiment for you.

Spend 3 minutes and 31 seconds scrolling on your phone. And then spend that exact amount of time listening to the song I've linked to below, which is not some epic masterpiece but simply a track recorded by an indy band a few years ago.

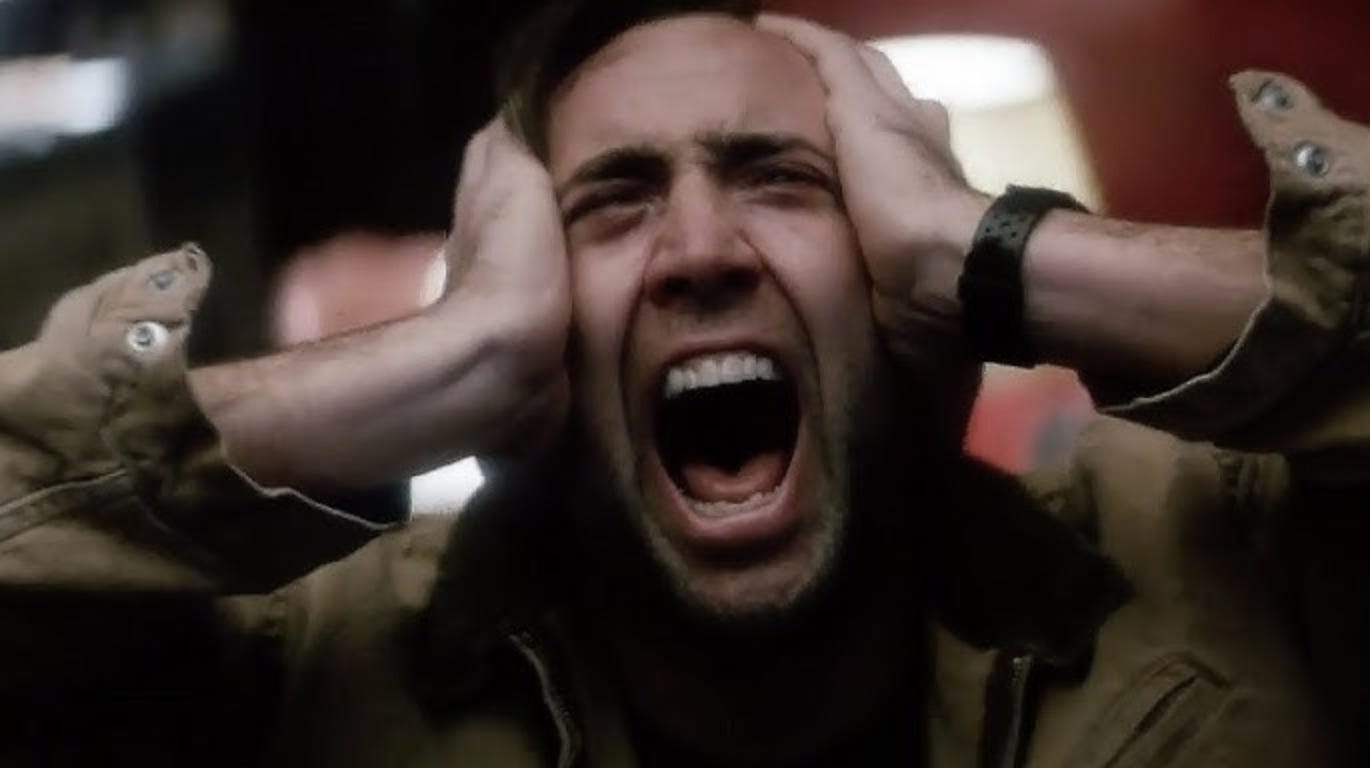

Alternatively, if music is not your jam, perform the same experiment with the film clip I've linked to below, which is a piece of delightful comedic insanity in which the actor whose mug I've featured throughout this piece confronts his younger self, as well as the shackles his career has placed on him.

Then ask yourself a simple question: which makes you feel more connected to reality, humanity, and the full strange sensation of being alive: the constructions you're experiencing on social media, or the constructions you're experiencing through art?

Reality is not breaking, friend. It's all around you. You just have to find it.

I don't care much for what I've read from Jia Tolentino and I can't stand Chris Hayes. They always struck me as the epitome that middlebrow, bourgeoise, expensive coffee-shop patronizing, trendy bakery frequenting, conversation-about-a-conversation having, shamelessly gentrifying, flagrantly privileged, desperate to cover themselves in the veneer of cultured intellectualism without actually putting in any of the work crowd that I absolutely despise. And even I was having trouble getting on board with some of the vitriol you were hurling their way, but you got me there by the end.

"Finally, we are at the rub. Because all of these people who are complaining about how reality is broken are, in fact, making plenty of money and chatting away on podcasts and raising kids and doing all the rest of it, and one of the main things they are complaining about is that they feel like they're under assault from other people's suffering."

This is when you won me over. These are people who incentivized and actively profited from what they are decrying, and even their complaints are almost entirely self-serving. What's the difference between some MAGAT who says that things were so much better in the 50's, 60's, 90's or whenever, when there was no such thing as racism or police brutality or discrimination of any kind, because they weren't hearing about it in their all-white, internet-less communities, and someone who complains that social media is breaking their brain because it gives voice to people who are actively suffering from injustice? It's the same egocentric worldview in which the value of a thing is determined solely by how much comfort it provides to the privileged. Hayes is almost entirely indefensible and Tolentino, from what I've read (and it isn't all that much) may as well be the poster-child for NPR. No sympathy indeed.

"1. People's phones have convinced them that they are functionally omnipotent beings who can know and opine about everything of importance in the world because every important thing in the world is there in their social media feeds."

I may not agree entirely with 2-5, but this is an objective fucking fact. I think there is a whole element of the role of the corporatization of media and its effect on the medium itself (with the corporatization of media comes the need for advertisers, with the needs for advertisers comes the need to allow space for ads, with the need to allow spaces for ads comes the need for concision in exchanges, with the need for concision in exchanges comes the need to only ever host people who present opinions that reinforce the status-quo or appeal to 'common sense' as opposed to people who challenge the status quo, as they would need space to explain why and provide evidence) that one could get into, with social media being a kind of refinement, but it ultimately doesn't matter. This is where we are.

And it's only going to get worse with the advent of AI. People legitimately cite ChatGPT and Grok as sources in official fucking documents. They rely on them to summarize books, studies and documents that they can then pretend to have actually read and understood. I've been in the same room as people who use them to fact-check, and to come up with rebuttals, which should be terrifying enough to anyone who knows how AI works, but particularly terrifying to someone with in-depth knowledge about any subject who has dealt with AI in any way, shape or form and experienced firsthand the countless factual errors it provides as so-called information and the way its prompt-based responses essentially make it into a gigantic confirmation bias machine.

Marshall McLuhan would be having a field day in 2025.